Hello there, you are reading Monday Map on The Busyminds Project. I write essays that explore the intersection between human behavior and knowledge.

For today’s essay, I run through the problems of learning precise things and scorning abstracts. I encourage you to learn metarules, follow your curiosity, and let it lead you. I write not what is useful but what I enjoy. So please, enjoy. But, subscribe first.

The Problem of Specifics

We love facts and specific details. We love them because they provide assurance, like a cushion for our minds against the misery uncertainty brings. For instance, learning details about the cause of a delay while waiting for a person reduces the misery associated with waiting. Uber’s placebo. But this is just one of many.

However, when we focus on details, we miss important information. Details are narrow. You have to zoom in. But this is not bad in itself except that details are interesting; interesting enough for us to keep us zooming in and losing awareness of what we are blind to. We learn so much details that we don’t know what we are not learning – what stands outside the window. Nassim Taleb said it best that we learn facts whereas we ought to learn metarules. He wrote in The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable that:

Another related human impediment comes from excessive focus on what we do know: we tend to learn the precise, not the general.

What did people learn from the 9/11 episode? Did they learn that some events, owing to their dynamics, stand largely outside the realm of the predictable? No. Did they learn the built-in defect of conventional wisdom? No. What did they figure out? They learned precise rules for avoiding Islamic prototerrorists and tall buildings. Many keep reminding me that it is important for us to be practical and take tangible steps rather than to “theorize” about knowledge.

We do not spontaneously learn that we don’t learn that we don’t learn. The problem lies in the structure of our minds: we don’t learn rules, just facts, and only facts. Metarules (such as the rule that we have a tendency to not learn rules) we don’t seem to be good at getting. We scorn the abstract; we scorn it with passion.

An observed behavior is usually backed by an unseen, sometimes abstract cause. To miss the information for the details is like Newton focusing on the apple and ignoring gravity. This is how intelligent and imaginative people reach first-principles.

We rail time and time again about how people behave and the effects of those behaviors. We spell out and complain about specific facts and details usually in differing contexts without asking what is going on in an abstract realm. We jump from facts to facts, stories to stories, details to details, and headlines to headlines. All the while investing our intellect and emotions into them. We dig into the details and refuse to zoom out. This is reasonable behavior because specifics are more salient, more attractive, more lurid, and more sensational than abstracts.

But in an ever-changing, complex, dynamic world, specific details have poor shelf lives. Learning them is just a little bit more important than entertainment. News is entertainment.

Our problem with moderation

But that is just one problem. The other problem is about doing things in moderation. This is pretty summed up as: we don't know when to stop. We seem to take what is good, or probably what works, and decide to take it to extreme (totalitarian) positions. It is like jam; we spread it on everything. (I still wonder in horror how people eat yam and butter).

More like:

“Everything in the jam, nothing outside the jam, nothing against the jam.

Benito Jamussolini

Due to a polarizing sense of good and bad - a mental distortion necessary for survival, we easily fall into extremes. Interestingly, fervor is associated with extremes, and nuance is associated with tepidness.

We apply this bread-spread habit to everything; but in this context, knowledge. Jonathan Haidt wrote in The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided By Politics and Religion;

"People who devote their lives to studying something often come to believe that the object of their fascination is the key to understanding everything."

A random Tweet; nothing serious or related. A joke.

But forget about 'devoting' ourselves. When we take a liking to something there is just the inescapable urge to paint everything with it. We wish to see it everywhere. Hence, moderation feels like we are being denied access to a toy. But the age-old wisdom remains: that too much of everything is bad.

"Too much of everything is bad"

Speaking of age-old wisdom. Are we not in our ever-changing world just recycling heuristics, sometimes making them look more sophisticated by adding a study or a theory into the mix? After all, philosophy is shit and science is king.

The wisdom of keeping things moderate has always been there. But we always by some theory of truth or another keep skidding towards extremities, abhorring moderates as centrists, cowards, and fencists.

However, there is no wise saying, no heuristic, no "theory" telling us how to behave that has not existed before now. Some of us just discover and rediscover them accidentally and we feel like we must spread the word. But there is one more problem.

Banality: “but we know that.”

As you begin to spread the word, the enlightened parties arise - Tobiahlike - saying, "but that's not new."

Of course, it is not new. Is wisdom useful only when new? In fact, the older it is, the more serious we ought to take it. After all, it has survived so many eras. To ask it differently, “is novelty the potency of wisdom?” or another form “does a banal saying lose its wisdom?”

This is what an original idea or thought means: not that no one has thought, spoken, or written about it before. Not that it does not exist somewhere in the universe. It does not mean that you are the first to talk about it. It is not “new.” Rather it means that you found it on your own through introspection and personal observations of the world. Most of which are accidental.

It is expected that when you see something that is perhaps unpopular but which needs to be said, and you attempt to articulate it, people will definitely say "that's not new." That is your sign that you have found something interesting all by yourself.

However, when you meet someone who says “but we know that,” check him. Check if they only know so in theory – which is just a fancy word for “talk” – or they practise it. Is it wisdom if you only say it and not integrate it into your life? (I’m okay with empty intellectual talk not posing as wisdom. Some talk is entertainment and that’s fine).

“But we already know that.”

“No, you don’t sucker. You just don’t want to be seen as not knowing.”

The problem of overcorrection

To the final problem. The problem of overcorrection.

So, now you have an extreme you are warring against. For instance, you are battling the pharmaceutical industry for their endless pushing of artificial medicines that seduce more people to rely on chemicals rather than naturalness. You are concerned and perhaps correct that they are doing this for capital gains at the expense of everyone’s health. You now advocate for people to get some sun and touch some grass. Except, of course, you don’t know when to stop. You do not know when to celebrate the wonders of the medical sciences. You do not know that “Mother” Nature is waiting to give your kids polio if you won’t give them a vaccine. You don’t know too much of everything is bad. You overcorrect.

Extremes do not have to fight extremes. Why? Because the world moves in contexts – the tide doesn’t repeat its flow. We are constantly changing forms and problems. A one-size fits is precisely dangerous. Easy, precise, but dangerous.

True, tribal instincts allow for social flourishing. But at the least, you should be able to admit to yourself that your tribe gets insane sometimes. You don’t have to drive to the end of the road to piss off your enemies.

Learn metarules

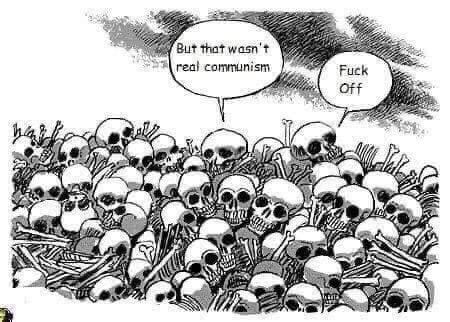

Just before you go off about how you hate commies, ask yourself why people willingly believe this thing you know is horrendous. Ask why people believe things you think are stupid. Consider that everything has its appeal. Without dealing with that appeal, you are only in a screaming contest (I hope you lose; miserably).

Watch out for moot points. Avoid overton windows. Allow your curiosity to lead you like a sniff dog to find out what is worth finding out. Throw away the popular arguments; find them again on your own outside the window digging. The thrill is in the chase, not the correctness. Vale.

Here is your picture though:

Have a great week.