You Will Find “It” Corrupting Too

Part Two response to David Pinsof's "You Will Find This Interesting"

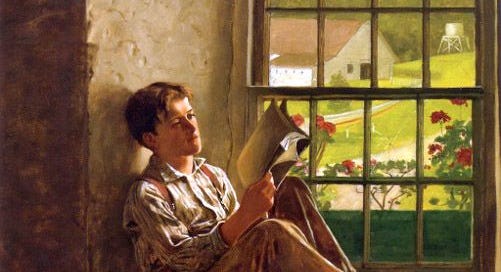

Aristotle said, some two thousand years ago, “All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves; and above all others the sense of sight.” Of this, I can make sense. It shoots straight like an arrow, not turning here and there; intuitive, axiomatic, and complete in itself, this is relatable in experience. For I know knowledge delights me; I take pleasure in knowing things. Therefore I take this as a common experience and take it in the spirit of Terence’s “I am a human being, nothing human is foreign to me.”

But this is not how I feel, nor is it what I think when I read the following words written by the author two thousand years later: “Our brains weren’t designed for solitary contemplation; they were designed for arguing, rationalizing, politicking, rule-following, covert rule-breaking, and excuse-making.” Unlike Aristotle’s quip, I do not find this straight or intuitive. Neither is it axiomatic nor complete in itself. I find this on the other hand shocking, jarring, surprising, disarming. But most especially I find myself asking what kind of statement or claim it is. Is it an argument, a rationalisation, a politicking, rule-following, covert rule-breaking, and excuse-making? Surely it must belong to one of these, and not to, say, solitary contemplation. Yet I can not tell. For all intentions, the claim is hardly justified.

Nonetheless, of the two claims, the reader may observe this distinction: the former captures men as a universal in a sense that allows each individual man some private experience. Aristotle speaks of all men as having a natural desire to know, whether as individual men, taking delight in our senses, or as a group of men having a natural desire to know and as a group taking delight in their senses. It is not so with Mr. the author whose claim of a “design” eclipses each individual man.

In Aristotle’s world, man desires to know, “even apart from their usefulness” of what they seek to know. the author implies otherwise, explicitly rejecting a design that favours solitary contemplation, and claims —if I am allowed to make it a quote—that “man cogitates nothing apart from their usefulness.” Thus, Aristotle pitches his tent with Homo sapiens, our author with Homo hypocritus —the man engulfed by the social gaze whose cognitive design renders him less than competent to do anything for himself other than what is useful in the social sphere. Homo sapiens delights in his senses and what he can take in. Homo hypocritus has no delight except by social advantage. Homo hypocritus is therefore a shrunken individual. And the author’s You Will Find This Interesting —like all of his MetaBullshittery—is an attack on the individual and his inner life. For whom I take up my keypad in defence.

With the attack on the inner life comes various attacks. In the same way damage done to a pregnant mother threatens the child in her womb. As severe blows to the mother afflict the child, so does an assault on the inner life afflict and attack various other human objects and concerns. I speak here of private enjoyment, rationality, beauty, goodness, authenticity, leisure, and the transcendental nature of truth. It is an attack on that vague property we call “essentially human.”

Of the author’s thesis, he argues that humans are primarily interested in bullshit. Where bullshit, “in the Harry Frankfurt sense,” —the author writes in the About section of his Substack Everything Is Bullshit: Poking Holes In The Stories We Tell Ourselves — “is different from lying. When you lie, you knowingly misrepresent the truth. When you bullshit, you don’t know or care about the truth; you just say whatever you need to say to get what you want.” Summarily, the author argues that humans are primarily interested, not in knowing or caring about the truth, but primarily in what they have to say or do that gets them what they want.

It is in this light he captures the topic of interestingness, claiming that “We’re mainly interested in bullshit. The more useless and outlandish the bullshit, the more we’re fascinated by it.” Thus illuminating ‘interestingness’ not by its essence —if there be any—but by our attitude towards the things we find interesting. And that attitude is the attitude of bullshit, a lack of care for the truth or in this case, the interesting object and rather a greater care for what you want. Said in another way, the author’s idea of the interesting is that of the advantageous and as we proceed, the socially advantageous rather than “useful truth.”

By eclipsing, not only man, but also the interesting with the social gaze, we can have only little to say of the things we find interesting. We cannot say of sports or a football game to be precise that the game was exhilarating, giving us ebbs and flows of really strong emotions; that it gave us funny palpitations of heart, the entire world seizing its breath as France’s Kolo Muani is clear on goal against Messi and Argentina’s goalie in the 118th minute extra time of a game where we desperately want Messi to win the trophy (which thanks to God he did). We cannot say enough of the relief we experienced when Dibu Martinez blocked what was certainly a goal by just 3 inches deviation. Whatever we have to say about what I have described prior; whatever we truly felt that is independent of social advantage gets raptured without trace in the thought that “we’re interested in sports, celebrities, and the news, even though they’re mostly useless. Everyone talks about these things, and we don’t want to be left out of the conversation.” Or perhaps we can say so, but only on a secondhand basis. Because if it is true that we are mainly interested in what we want —in this case what we want is to not be excluded—then it matters less what we genuinely felt in that world-suspending moment. Therefore I find it unsurprising that the author’s essay says nothing —nor can it— about the quiddity of interesting things, of their intrinsic value.

Suppose you read a joke, which being truly funny, made you laugh, you sent it to me, and I responded “You only find this funny because you want me to think you are cool,” how would you feel? If I am a human being and nothing human is foreign to me, I wish to guess that your answer is that you will feel deflated. The pleasure you got from reading that pleasant joke turns sour. Yet this is only one feeling, the first one. I suppose the other one is confusion. You may begin to ponder if the joke is truly funny or if you are merely pretending. You will be divided between a voice that tells you that something about the joke is funny. But at the same time, pondering your friend’s comment, you are unable to enjoy it as such.

If this is true; if I have gotten at least close to describing the processes playing in your inner life, I then may be fair to hypothesise that there is a humorous quality in the joke you have read that is independent of your enjoying it both as a private individual and a fellow seeking his friend’s esteem. Which if we were to consider the implications of this hypothesis, we may begin to observe that interesting things —be it sports, celebrities, fiction, news, Capital In The 21st Century, ‘9 Creme Eggs In The Bum’—have ‘something’ about them and in themselves that stands back from social advantage. We need ask, “Do I find this joke funny or am I seeking merely to impress my friend?”

Now, I grant that we may not be able to arrive at things via the front door. So we must use some other means; perhaps the window. Like, for instance, trying to arrive at what being interesting is by contrasting it against something else. Thus he performs this permutation below:

“Maybe the answer is usefulness. Stuff is interesting when it’s relevant to your life—when it helps you get what you want and make practical decisions.

Or maybe the answer is truthfulness. Stuff is interesting when it’s accurate or insightful—when it reveals the full nature of reality, in all its subtlety and depth.

Or maybe the answer is both! Stuff is interesting when it’s useful and truthful. You’re trying to gain knowledge about how the world truly works, so you can use that knowledge to get what you want out of life. It’s like an equation: Usefulness + Truthfulness = Interestingness. Right?”

Which provides a negative that: “Wrong. Useful truth is boring. Practicality is ponderous, subtlety is soporific, and depth is dull.” And afterwards provides the contrast we need to polish the claim that “The quest for knowledge, the search for wisdom—it’s just a story we tell ourselves. We’re mainly interested in bullshit. The more useless and outlandish the bullshit, the more we’re fascinated by it.”

Summarily, our author states the claim —or is it the false claim—our human desires make of themselves as being interested in things primarily because they are true or useful and proceeds to demolish it with the counterclaim that the usefully true things are boring therefore we are not often interested in them.

Without flattering the reader, I think it is self-evident what both concepts of the true and the interesting have in common so far per our author’s analysis. That useful truth is boring and interesting things are socially useful without being true. He supports this with a hefty list of false and useless things we are interested in and the truly useful things we neglect: fiction as against reality, tabloids as against scholarly journals, celebrities and athletes we can never meet, sweeping generalisations opposed to complicated reality, eloquence deviated from truthfulness, spiritual flimflam, contrarian takes, tax codes, how cars work, retirement planning, actual congress policies.

Yet, all in all, something begins to shine. Something essential. Perhaps something not intended. Still, something not negligible. That thing being the concept of usefulness: while useful truth is boring, ‘useless’ interestingness is useful. Useful, as in socially advantageous; as he finally defines, “So what makes stuff interesting? Any information that helps us get what we want from the people around us, including the ugly things we can’t admit we want.” And the ugly things we want? Here: to fit in, attention, to form cliques, to display our superiority, to display our group’s superiority, to persuade people, etc.

But I hope the reader is paying attention. For all these things do not tell us something is interesting. They do not say whether we find it or them interesting. They merely explicate motives. In other words, they are comments on our thoughts and motives and impressions rather than the circumstances or objects external to ourselves that would normally remain so more or less if left independent of our considerations. The author says nothing of the structure of reality and the demand it makes on our rational apprehension. Rather we are restricted to our motives, locked into an egocentric state of mind. To recall our 118th-minute chance of ruining Messi’s World Cup chances, the author’s “stuff that makes for interesting” does not capture the exhilarating power in that gameplay in and of itself. It steps outside it, forgetting it, annihilating every concern about it, eviscerating it, to conclude instead that we care for the social movement of the gameplay. You can still say it this way: you don’t care if something is actually interesting or not, you only care whether it brings you what you want.

It appears then, that the measure of truth and the interesting, per our author, is the concept of usefulness; of utility; of something capable of accomplishing ends other than itself. Unlike Aristotle who believes men can delight in their senses; “for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves,” the author sits firmly on an island named Utility and he judges everything from there.

Having absorbed both the individual and the interesting into the social sphere in totalitarian style, the question thus raises itself as to the predicament of truth and man’s rationality. If the individual cares not for truth but for the useful and social usefulness of truth, of what claim is man’s rationality which the philosophers of old claim is the apparatus for apprehending truth? The answer, according to our author, becomes “rationality? No, man is a rationalising animal.” A statement which, if you are attentive, you may easily find the traces of its truthfulness in the most innocent of our species —young children. Who know how to —to borrow and modify the author’s terms— argue, rationalize, politick, rule-follow, covert rule-break, and excuse-make by simply being thrown into the vast vat of the human social world. Children know how to lie without being taught; they seek to escape punishment. In this sense, children are not even bullshitters in the Harry Frankfurt way. They are liars who know the truth. But let’s agree that they exhibit this “design.”

Nonetheless, this attribute is not a sweeping factor. Nor should we let it metastasize via our language as our author has so done, being guilty of reductionism, taking a part for greater than what it is, risking the whole. This is how the inner life gets demeaned.

For without the inner life, without the individual, the interesting becomes a vague nebulous character of our world. It becomes a means that cannot recognise itself neither can we do so. For if there is no room to stand back and delight in our senses apart from their (that is what we know through our senses) usefulness, there is no room left for private enjoyment. But what is the concept of the interesting without delight, without pleasure? No one has ever declared the interesting to be about use save the author. Which he arrives at thus: ““Interesting” is not the same thing as useful or accurate.” However, we see the dominant impulse of his thoughts when he advocates that “we can try harder to make them the same thing—or at the very least, learn to tell the difference.” One wonders what it is about the useful that seeks to bring everything under its canopy or tries to spot what it isn’t and force pariahship on it.

Of the inner life, and the delightful, and the intimate, I recall a fairy tale titled The Iron Shoes. Compiled in Franz Xaver Von Schonwerth’s The Turnip Princess and Other Newly Discovered Fairy Tales, The Iron Shoes is the story of Hans, the burdensome son of the king’s groundskeeper. Who giving his father so much trouble, caused the man in rage to say to him: “Why don’t you just beat it, and let’s hope that you learn some sense by going out into the world!”

Hans took his father’s angry advice and went into the world. As in all fairy tales —if you can spare the generalisation— he discovered, one evening, an old castle in some overgrown woods. Where he found many empty rooms. Choosing to rest in one of those rooms, exhausted, a woman dressed in black came, brought food, gave him drink, pointed to a bed, and left without saying a word. At midnight a vicious man in black walked in, and he tortured the boy and tried to choke him.

The next morning, the hospitable woman came with food and drink as well, just this time dressed in gray. She left without saying a word. That night, two men appeared and tortured him even more cruelly than the man from the night before had. The boy made up his mind to leave and packed up his belongings in the morning. Just then the woman, this time dressed in white, entered the room. She asked him to spend just one more night there. He did. As you would expect, three men came that night and dealt violently with him, performing Wrestlemania moves on him. An hour later, the luminous woman in white reappeared with thunder and lightning in the air and drove the brutes away. It turned out that she was a cursed princess whose curse had now been broken —it seems by all that Hans endured. She rewarded him with herself as his bride, with much wealth, and many servants.

Yet Hans, yearning for his father, begged leave of his wife to go see him. A kind woman, she set him on his way with a ring. With the instruction that if anything was to go wrong, he merely needed to turn the ring and she would be there. Hans then rode away. But not without a stringent warning: “Be careful, and don’t use it to summon me if it’s not necessary.”

His father could not recognise him at first. His son was nobility now. Afterwards, Hans introduced himself to the king who organised a ball in his honour. At the feast, all the knights danced with their wives while Hans was not allowed to dance with anyone for they were all jealous of his good looks. He told the knights of his stunning wife. Of how her beauty superceded all their wives’. But they mocked him. Taunted and annoyed, Hans turned the ring.

In rolled the beautiful princess’s carriages and entourage. Stunning the crowd. Taking her arm, Hans danced with his wife before everyone’s eyes. That would show them. His prestige restored.

When Hans awoke in the morning, his wife had abandoned him, laying out his old clothes, a pair of iron shoes and a letter that said “I’m punishing you by leaving. Don’t try to find me. You will never discover where I am, even if you wear out these iron shoes.” He turned the ring to no avail. Ashamed, he fled and started seeking out his wife.

Skipping now many other details of his journey, Hans arrived at his wife’s ongoing wedding ceremony to another man. But using an invisibility cloak he had picked up on his travails, Hans interrupted the wedding, slapping the book from the officiating minister’s hands and slugging the groom in the mouth. Eventually, Hans’ ring gave away his identity to the princess who, overjoyed to see her husband again, made up with him, and then they had a real wedding. End of story.

Of the inner life and the intimate, the author says we are Hans. Displaying our figurative wife’s beauty because as in Hans’ instance, it signals our superiority to the other knights. But right there also we see the punishment. Of being unable to continue enjoying the delight. He loses the wife he had won through three nights of torture and terror. It banishes itself from our presence, needing diligent seeking and a semblance of serendipity to find it again. For the best place to delight in one’s wife is in the inner room; a chamber made for intimate relations, deliberately constituted to shield off peeking eyes and voyeurs. What use is such a chamber to someone who thinks the beauty of his queen —as in Xerxes and Vashti —is for entertaining his noblemen? If we are of a healthy mind, we will disapprove of such a gesture.

But perhaps the wife analogy is too intimate. Yet consider; consider what is left of something you love, a sport or a show. Consider that whatever you are experiencing is good and delightful in and of itself. But you cannot enjoy it because others are not there to see you enjoy it and draw inferences that elevate your status. Imagine solving, after so much difficulty, a tough math problem. But you cannot congratulate yourself because “if a tree falls in the forest and no one hears a sound, did it really fall?” Imagine that after learning the intricate workings of classical music, knowing how notations work such that you now genuinely appreciate Beethoven’s genius, you have to then endure barrages of accusations that you are being pretentious. I bear no grudge for the social aspect of man. But we are doomed if its gaze is all we have.

Contemplate the shy girl, who gets bullied for not fitting the beauty standard of her day. Who then finds rest and reprieve in her room delighting in Harry Potter and his gang of mischief-makers running down Hogwarts’ hallways. I imagine the contrivance that would ensue in her if she suddenly starts to think this way: “I do not really find these books interesting —despite how much they make me happy—because it does not afford me those ugly things like fitting in with the mean girls. Nor does it signal my superiority.” I bet she will pierce herself with many sorrows and her leisure will furthermore be a realm of turmoil.

For there is no interestingness first and foremost without leisure. It is when we have stepped back from all the strivings of the social sphere that we get to find delight in things which contain them. It is when you do not desperately want someone’s approval that you can determine if the person makes good jokes or if everyone pretends to laugh. For we live in a world that has no scarcity of grovellers. Folks who laugh, knowing well enough that it is not funny, at a rich bore’s crass jokes for the sake of “getting what they want.” I invite the reader to interrogate: when have you been more forced to lie, be dishonest, or compromise your values? When you are simply looking for delight in things and people or when you are seeking advantage?

Consider a boy who takes a girl to a Stand-up performance for a first date. When is he more likely to fake a laugh? When he is truly interested in amusement or when he is angling to make a good impression? If the former, common sense dictates that he pays attention to the jokes; to the comedian’s narration. You will find him attentive, following the rhythm and pulse of the MC. If the latter, he withdraws attention or at least scarcely pays attention to the performance and watches with his side-eye for chuckles and suggestive body movements to pick up cues when his lady laughs, that he might laugh as well. In which case we can say he is not interested in the performance. The performance becomes for him an onanistic object of an ulterior desire. But at least it is clear, even if he says otherwise, that he is not truly interested in the performance.

If, however, both the man and his lady are genuine stand-up comedy lovers, you will find that they will both pay rapt attention to the performance. Of which they will get the best experience, being delighted in their senses apart from the usefulness of what comes thereafter. Walking home together, they are sure to have the best time together. They will make references that both parties can readily understand because they were both attentive to the rhythm and beat of the show. They will relive punchlines and climaxes together, having double the delight even as they inhabit a shared solitude.

Surely this is what we do when we share pieces of things we love with people —especially people we love. We invite them into our world. To see things as we see them. Not primarily for them to think well of us. But to think well of what we are showing them. Sometimes we do it for the people we love. We know that what we are showing them is good for them. Perhaps it is able to make them laugh, rescuing them from a sombre mood. Like an immigrant’s toddler who brings a flower for his weeping mom after she endured a humiliating day at work all day. What does the toddler think as he hands her the cheerful flower? To make her think well of him? Perhaps so, for she might transfer her aggression to him or anyone else in the house. Or could it be that he genuinely cares for her and he primarily wishes to lift her mood?

Of the two reasons, if your impulse drives you to posit the first strongly over the second, I don’t have good news for you: you have a morbidly cynical mind. But I guess —for if I am a human being and nothing human is foreign to me —that even if you hold strongly to the healthier option, the author’s essay disarms you by explaining your delights more cynically. Now this is the essay’s appeal —and that of the Everything Is Bullshit philosophy (Meta-Bullshit).

For if the inner life is the site of private enjoyment, a place of rest and leisure, of relief from the social gaze, Meta-bullshittery attempts to expose that inner sanctum to the piercing eyes of the social sphere. For if and truly if man is Homo hypocritus; if all is subsumed by the all-seeing eyes, anyone’s claim to enjoy anything that is not primarily for the social gaze must be lambasted as pretentious. Thus, the rationalists, scientists, and philosophers must enjoy their pie of bashing which comes served on the platter of someone telling us what and how they think the rationalists, scientists, and philosophers think. Or who have you believed, after seeing the all-important truth of Meta-Bullshittery, between the person who loves truth for its own sake and the one who claims the person who loves truth for its own sake is merely bullshitting? Even Aristotle now by all measure is a bullshitter. Who cares for all men desiring to know? What archaic thought!

His essay then becomes a kind of police whose duty is to tear down every shower curtain, destroy every bedroom door, in short, destroy everything that allows people a claim to private thoughts and enjoyment. The yanking police comes to pull away the shower curtain with a warrant; “who says you can use a shower curtain you bullshitter?” For if everything is bullshit, there is hardly any truth but pretence. For you cannot truly realise your bullshit and genuinely continue. But “genuineness?” How is that a thing when everything is bullshit? Under the reign of Meta-bullshittery, solitary contemplation or a claim to it is nothing but practising to pretend, rehearsing arguments in private moments, rationalisations, politicking, excuse-making that you might deploy later when you stand facing “the group.” You don’t enjoy jazz. You possibly could not: you merely practice enjoying it so that when you find the moment and the people with whom jazz earns you some advantage, you will not technically be lying to them that you love jazz —after all, you have done your homework. Under Meta-bullshittery, nothing has a value, only a price. This is onanism at scale; mediated masturbation if we are frank.

But I am a human being, and nothing human is foreign to me. Thus I believe this onanism is not so. I have myriads of things I find interesting for their own sakes quite apart from their usefulness. I find good books interesting of course, even and especially when done in solitude away from the penetrating and questioning social gaze. I find football interesting —it is called the beautiful game for a reason, with its imperfect simulation of the thrills and the sinking feeling of war (of sports, Jon Haidt says sports is to war what pornography is to sex). Good music is delightful so I find it interesting. I know this because when I struggled to sleep some nights ago, I played some sonorous sounds from a playlist and was soon adrift. All of which happened in the confines of solitude, with the apparatus called my inner life which is capable of reaching out to delight in all that invites my interest.

Or perhaps these are the stories I tell myself that our author attempts to poke holes into. However, I wonder what will be left of our fabrics when all we have are holes. I also wonder about the appeal of poking holes in things. Is it chic? Perhaps: the author himself alludes to it. This would imply that the author himself is as guilty as the rest of us: he does not deny this.

This, however, now brings into question a moral consideration (although the reader must be aware that the moral considerations in the essay under purview are manifold; it will take a lot to address them). For the true and good purpose of poking holes in things is so that we can mend them. When we catch ourselves bullshitting —which is different from lying—we should endeavour to retrace our steps back to the whole truth. But truth, what is truth? What is truth to a brain designed for arguing, rationalizing, politicking, rule-following, covert rule-breaking, and excuse-making? Definitely, truth must be alien to such a brain design. Except of course truth is that which is useful —tax codes, how to repair an engine, retirement planning, etc. All of which are insignificant apart from their usefulness other than when they are ennobled by some incidental nerdry.

But what moral consideration can be weighed on the scales of tax codes, engine repairs and the category? We seem to have narrowed ourselves into a narrow strait; nothing existing outside the boringly useful. Nevertheless, this is not the worst moral consideration.

The worst there is is the fact that this joy of ‘poking holes’ corrupts and contaminates good men and women. People upon reading this essay, if they are not philosophically sophisticated, will lose their innocence. Folks who truly enjoyed things unpretentiously now have to revise their motives multiple times to ascertain one act. Remember the joke you found funny? Now if you revise, you find it hard to enjoy that joke as much. If things are so bad, you may capitulate to the charge that indeed you are a cynical person; that your entire life is built on and around bullshit.

But let us acknowledge that many times we come to things for the sake of the ugly things. For I believe it presents the finest instance —that we might put it to bed—of enjoying things in themselves. I present to you my story of how I came to support Arsenal Football Club.

Born last of five children, my social setting was prepared for me, my parents and siblings contributing to shape my tastes and desires. One of which was a football club. At the start, I supported Bolton Wanderers because of a Nigerian Jay-Jay Okocha who played at the time for the team. But my support for Bolton was weak. I didn’t care for their games; I cared only for Okocha. This support was short-lived. After which I drifted towards FC Barcelona of Spain, charmed by Ronaldinho’s flair and Carles Puyol’s leadership. I imitated Puyol’s movements as I kicked a football around our living room alone —no one being there to observe most of the time. I enjoyed it.

But my fortunes changed the day I picked up a CD my brother owned. He owned it —alongside the original jerseys, the monies spent, and hours discussing the club— because he was passionate. That passion and enthusiasm were inviting. So I, for how many hours I cannot now remember, watched The Best of Thierry Henry, a video compilation of his first 100 goals for Arsenal Football Club. This was beauty first-hand. Enthralling. I might have wept tears of joy, sealing my fate and allegiance with that club. I was adrift before then but I found my home. I watched their games, staying up at night sometimes to do so, waking up late for school. They played beautiful and elegant football and have since left a longing on my palate. I saw them win sometimes. I have seen them lose many times. Hurtful losses —especially to Chelsea Football Club. I have endured disgraceful things with that club for nearly two decades; especially when we had a nine-year trophyless run until that night in May 2014, a year after the person whose passion for the club brought me to it died.

All these to say that we might indeed be driven to find things interesting because others do. But this is not ugly. Instead, it is the case that through imitation we develop our senses to find true delight in things. Which happens to all of us. For coming to find things truly interesting, even though we came to them through other people, is to see it and judge it for yourself. In Eli Siegel’s words, “the deepest desire of every person is to like the world on an honest or accurate basis.” This is not only an aesthetic duty but also an ethical one. As Siegel says, “The need to be aesthetically just is an ethical need. To see something as beautiful, or say it is, when it isn’t —because our acquisitive ego saw it as most convenient that way—is ethical ill-doing, along with aesthetic ill-doing.”

This then brings us to a consideration. The consideration that the interesting is —as the author truthfully finds—neither useful nor true. The interesting is aesthetic. Be it in the news, celebrity culture, fiction, eloquence, and the litany of useless things Mr. the author finds surprising that humans are interested in. What we seek in these things is delight. Whether pure delight, religious awe, or morbid attractions, it is all about delight.

Therefore there is no speaking of the interesting without first carving out the place of the aesthetic. The place for delight. The place where for Aristotle, men delight in their senses. The inner sanctum fit for solitary contemplation. And there is a place for the useless: it is where humans are relieved from their everyday concerns of utility to enter, even if it be for a moment, into a palace of delight. Where they are free to “be themselves” and avoid scathing judgement. For even in knowledge seeking, as detailed by Abraham Flexner’s The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge:

“Hertz and Maxwell could invent nothing, but it was their useless theoretical work which was seized upon by a clever technician and which has created new means for communication, utility, and amusement by which men whose merits are relatively slight have obtained fame and earned millions…The mention of Hertz's name recalled to Mr. Eastman the Hertzian waves, and I suggested that he might ask the physicists of the University of Rochester precisely what Hertz and Maxwell had done; but one thing I said he could be sure of, namely, that they had done their work without thought of use and that throughout the whole history of science most of the really great discoveries which had ultimately proved to be beneficial to mankind had been made by men and women who were driven not by the desire to be useful but merely the desire to satisfy their curiosity…"Curiosity?" asked Mr. Eastman. "Yes," I replied, "curiosity, which may or may not eventuate in something useful, is probably the outstanding characteristic of modern thinking. It is not new. It goes back to Galileo, Bacon, and to Sir Isaac Newton, and it must be absolutely unhampered.” I reiterate: the attack on the inner life is one on “everything human.”

Finally, I approach my closing comments. If not, I would be doomed to write this forever. For there is still so much more to unpack. Like in the fishbait that reeled me into this boat, which I find contrary to truth.

In the fishbait paragraph of which I am fish, the author writes so:

“If there’s one thing that’s preventing us from connecting with our fellow human beings, it’s this perverse obsession we have with being interesting. We’ve convinced ourselves that if someone is boring, they’re not worth our time. The lust for interesting conversations has doomed us to a life of social alienation. We’d rather listen to a podcast than talk to our families.”

Having seen this essay various times after passing by, I finally decided to read it because I found the paragraph interesting enough —that is, it invited my interest. For I am concerned about connecting with our fellow human beings; about achieving true communion, where communion strongly supercedes the “ugly things” in the author’s lineup.

However, I met nothing but sheer disappointment as I progressed in the essay and arrived at the concerned portion; only to be doubly disappointed. But it is only to be expected that the conclusion has flowed from the preceding string of arguments and observations. Therefore I must now set the record straight and state what prevents us from connecting with our fellow human beings.

The author says that “if there is one thing that’s preventing us from connecting with our fellow human beings, it’s this perverse obsession we have with being interesting.” Contrarily, it is the author’s idea of “usefulness” and getting what we want from others that prevents us from connecting with our fellow human beings. It is the idea of wanting to form cliques, display our superiority, signal, to be flattered, that blocks the chances of connecting with our fellow human beings. In the author's own words, it is the lust for the interesting, where the interesting is “Any information that helps us get what we want from the people around us, including the ugly things we can’t admit we want.” It is not about the “interesting” as an aesthetic object but lust for ugly things if the author is consistent. The interesting things —for whom in this case we have no real desire— are merely means and not ends. We do not have a shortage of people who grovel, laugh at genuinely bad jokes, censor the truth in themselves, and compromise their values just to get a sniff of the inner ring and all those “ugly things.” And I call the reader to evaluate it; evaluate the best connections you ever made. I will bet that you connected best with someone over something you genuinely enjoyed and was delighted in; where you held your impulse for advantage in abeyance to live in the moment, delighting in the interesting objects alongside them; where you were most true to yourself by getting feelings which were your feelings about outside objects, about people, about music, events, poems, books, countries, statements.

It was in enjoying Marvel movies together, Taylor Swift together, that this other person began to shine in your eyes suspended from every acquisitive drive. We do not see and assess people well when we are desperate for what they can give us. For, to cite Siegel one last time, “When we are false to our greatest desire, the desire to see the universe for ourselves, we are false to other people too.”

It was when you knew that being with such a person doubles the joy you get from the peculiar object but never halves it that you struck the best connections. It was that moment when you said to someone, “You too,” on a matter you felt isolated in that you made the best connections. I ask the reader to evaluate.

You have instead failed to connect with your fellow human beings because you have been uninterested, not because you have been disinterested —that is, placing delight before advantage. It is not because of interestingness but because you have been obsessed —perversely so—with social gains; whether digital, pecuniary or other forms. You have elevated the ugly things over real people failing to treat them as ends in themselves.

The author says, “We’ve convinced ourselves that if someone is boring, they’re not worth our time.” But the counter instance is truer. We have convinced ourselves that if people cannot “help” us get the social advantages we want out of life, they cannot help us. People have chosen the company of rich bores over interesting poor people in the hopes that the social advantage will rub off on them. Therefore, if I avoid a rich bore, it is not because I do not think he cannot help me. It is because I think his money is not worth a dull spirit nor do I think I have the conscience to laugh at his bad jokes. Much more people have capitulated to rich bores than there are who dismissed the rich bore as no use. Interestingness is a statement of delight not advantage. People can be useful without being delightful and you could choose delight over use unless you worship at a cynical altar. After all, people drift towards podcasts more than their families because they believe the podcast can help them while their family cannot. It matters less that their family might be more delightful.

To “endure” a boring person is not connecting with them. Which often ispretence the case with people who you need to get what you want from them. You do not connect with anyone who is primarily to you means not ends. You are using them and your “connection” is a pretense. That's neither connection nor friendship. For, per Cicero, “pretence obliterates truth, without which the name (concept) of friendship cannot survive.” Neither the “peaceful stillness of boredom” as prescribed nor usefulness as hoped by the author makes for good companionship. Rather it is delight, learning to delight in the other that sponsors communion.

Lastly, on the inner life, and what it affords communion, like a mother accommodates her baby in the womb, Zena Hitz comes to boot: “The removal of intellectual life from the world, the withdrawn person’s independence from contests over wealth or status, provides or reveals a dignity that can’t be ranked or traded. This dignity, along with the universality of the objects of the intellect—that is, that they are available to everyone—is what opens up space for real communion.”

If the social gaze is all we have, it would explain why some people cannot enjoy things alone. But if not, it means these people are hollow on the inside. And to these people —and to everyone who reads this —I offer Peter Dale Wimbrow’s Man In The Glass as a succinct response to the essay in consideration. Your brain may not be designed for solitary contemplation, but I believe in miracles. Thus I ask you to contemplate the poem:

When you get what you want in your struggle for self And the world makes you king for a day Just go to the mirror and look at yourself And see what that man has to say.

For it isn’t your father, or mother, or wife Whose judgment upon you must pass The fellow whose verdict counts most in your life Is the one staring back from the glass.

He’s the fellow to please – never mind all the rest For he’s with you, clear to the end And you’ve passed your most difficult, dangerous test If the man in the glass is your friend.

You may fool the whole world down the pathway of years And get pats on the back as you pass But your final reward will be heartache and tears If you’ve cheated the man in the glass.

Once more, if we have nothing preserved from the social gaze; no inner life, no love of truth, no delight and solitary contemplation, we are nothing but, per Eliot, “the hollow men/ We are the stuffed men/Leaning together/Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!/Our dried voices, when/We whisper together/Are quiet and meaningless/As wind in dry grass/Or rats' feet over broken glass/In our dry cellar.” Vale!

This is the second essay of two parts. Read part one here

Thank you. A very big Thank you.

I read this in one sitting. Clap for me.