You Lazy Athenian

Write to first trap your ideas; making them stand naked before you, losing that fluid and euphoric quality that is begging to escape, such that you are now sure of what they are

“People who love ideas must have a love of words,” Beatrice Warde said. “Through writing, a thought loses its vague and aspirational quality, and stands fully clothed in imagery and nuances.” That is how Roger Scruton puts it. And most necessarily, writing is how we connect the dots. So, the way I see it is that anyone who loves ideas—or at least claims to do so—must love words. But how does this answer any question on why you should write?

For a while I loved the Athenians as described in the Bible; in the book of Acts chapter 17 verse 21. The passage describes the Athenians as always visiting the Agora to hear what the latest ideas are. But now I don’t think I love them that much anymore. For people who loved ideas, they seem pretty lazy. And that is disappointing. Because to me, why stop your love for ideas by listening to them? Why not advance your own? Also, if you are always listening to new ideas, you might just be living that life, as Scruton describes, of “uncompleted gestures, half-formed thoughts, and unplanned explosions of emotion.” A lazy Athenian clearly has poor thinking habits. Now I think it necessary to find out, if anyone says he loves ideas, whether he is a Socrates—someone who advances ideas. Or he is a lazy Athenian—content with merely listening to the latest ideas.

Yet, this does not answer the question ‘Why write?’

After all, if words are the clothes ideas wear, oration includes words. Spoken dialogues—Socrates at market square style—uses words. I converse all the time. I debate. Or worse, I tweet. Why narrow it to writing? In fact, why are you so obsessed with writing?

Beatrice Warde continues: “And that means, given a chance, they will take a vivid interest in the clothes which words wear.” In other words, given a good chance of advancing your ideas with words, writing has an added, silent advantage to speaking, or oration, or conversation: writing preserves the beauty and deliberation implicit in its practice. A conversation is like time. It passes. You will never have that precise moment again. Heraclitan style; “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man.” No two dialogues are the same. No two orations are the same. Only writing preserves the first and initial beauty of your ideas through time. Writing is the snapshot of thought.

Schopenhauer, in On Authorship and Style, makes good on expanding on the classical distinction between form and matter; between style and content. Where matter is a subject, a topic. It may be a general topic like insects or football. Or it may be very specific and unique like dissertation topics. While form is how you think, or present that subject. In this sense, you may present a general subject in a unique style. After all, Schopenhauer makes clear, that, “The three great Grecian tragedians, for instance, all worked on the same subject. So that when a book becomes famous one should carefully distinguish whether it is so on account of its matter or its form.”

The pleasure of writing is obtained from the pleasure of mixing matter with form. Still Schopenhauer, “style is the physiognomy of the mind.” Or as Roger Scruton describes, “a representation not only of the facts that inspired it but also of the person who gave voice to it. So clothed, a thought becomes what Henry James called ‘felt life.’”

The pleasure of writing is observing how it preserves the mind’s posture on a subject like a photograph memorialises one’s pose before a camera. In other words: what have you thought about the subject?

The lazy Athenian has never thought about the subject. He has only heard them. And he satisfies himself with the thought—the irony—that hearing about a subject is the same as having thought about it. He hides behind the elocution of the man who brought the idea to town and reports it in a way that you know that those ideas, although received, have not actually passed through his mind. Now I no longer love the Athenians.

Still, why write? Why not be like Socrates, half-naked, barefoot, accosting the next passerby, the next pious fellow, or the awesome Phaedrus and advance your ideas?

Well, because without writing, there is hardly Socrates.

Assuming that Phaedrus is our lazy Athenian, and Socrates is our feisty one—hot with ideas. Their conversation was preserved only through writing. We know what Socrates thought on the subject—Lysias’ speech on love and beauty—because Plato wrote it. In other words, the form and matter of Socrates’ conversation with Phaedrus only exists like a photograph because it was written.

Still again, consider that Socrates disliked the invention of writing. Speaking vicariously through Thamus, Socrates commented that “Trust in writing will make them remember things by relying on marks made by others, from outside themselves, not on their own inner resources, and so writing will make the things they have learnt disappear from their minds. Your invention is a potion for jogging the memory, not for remembering.” He regards this as an indictment. He compares writing to a painting; “because there’s something odd about writing, Phaedrus, which makes it exactly like painting. The offspring of painting stand there as if alive, but if you ask them a question they maintain an aloof silence.”

But suppose that I want to jog my memory of how I looked when I was a child. I would find a picture of myself at five years old. I could also take a picture of my current self and compare it to the picture of my five-year-old self. I can then compare and notice what changed. I may do the same thing with my ideas. I can, by checking the snapshots of my thoughts from two years back, check the current form and content of my thoughts. And I may smile or frown at the changes.

You see, my dear Athenian, ideas are fluid; like floating spirits. They are unstable and aspirational. And euphoric. Always seeking to escape from one form into another; making it always the case that we are not always certain what we think about a subject. We think we know. But like clouds, what we think we know quickly passes. We quickly forget them. Socrates says writing the things we have learned will make them disappear. I say that they will disappear anyway. Why not write?

Write to first trap your ideas; making them stand naked before you, losing that fluid and euphoric quality that is begging to escape, such that you are now sure of what they are. Then you beautify them with words you deliberately choose so that they might reflect the person who has thought them to life. This beautification is what we call style. Style, once again, Schopenhauer says, is the physiognomy of the mind.

Writing is a creative act. It is how we trap the ghosts of our ideas in an embodied form. Only lazy Athenians prefer the euphoria of being possessed by spirits. They have no love for creating them.

One must love writing because they love the process of making things beautiful as much as they love treating ideas. When the love of making beautiful things—via writing—meets the love of ideas, you exit that “life full of uncompleted gestures, half-formed thoughts, and unplanned explosions of emotion.” You come alive. You cease being a lazy Athenian.

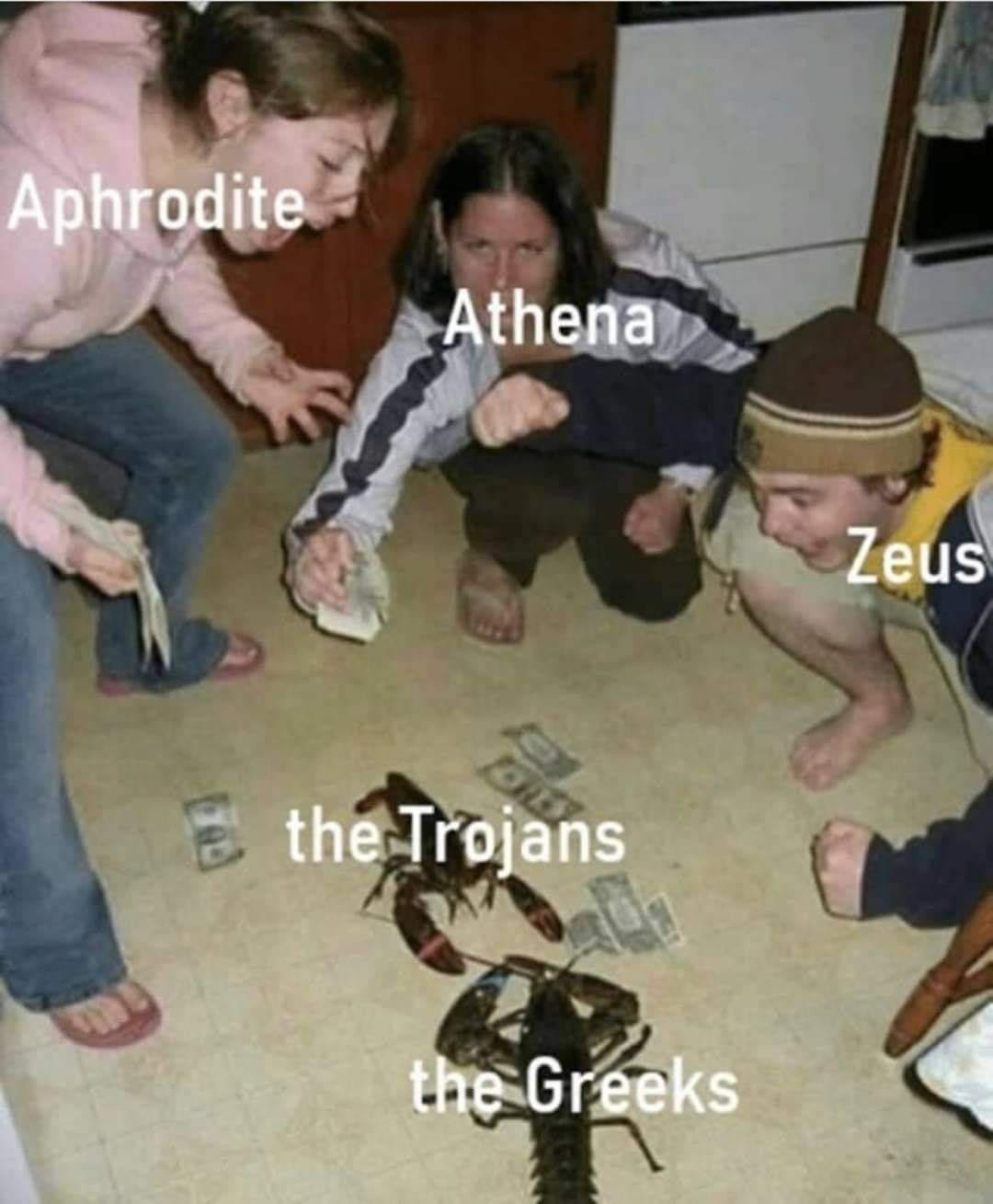

You thought I wouldn’t give you a meme? C’mon, you might be a lazy Athenian but I don’t hate you. So here goes: