For the Curse of Water has come again because of the wrath of God,

And water is on the Bishop's board and the Higher Thinker's shrine,

But I don't care where the water goes if it doesn't get into the wine.G.K Chesterton, Wine and Water

“There are, first of all, two kinds of authors,” Schopenhauer writes: “those who write for the subject's sake, and those who write for writing's sake. The first kind have had thoughts or experiences which seem to them worth communicating, while the second kind need money and consequently write for money.” These opening sentences to On Authorship and Style allow me to see once and for all why I have little fear of what ChatGPT and its other kin bring.

Marvelled as I am, I do not for once think the human distinction is under attack. For I have held for a while now that people who live in the presence of muses do not have to be afraid of this ingenious piece of human creativity. When writers are obsessed with making beautiful things, an excess of counterfeits will encourage, rather than discourage them, to keep producing beautiful things. They understand intuitively what Paul said to Timothy “No longer drink water exclusively, but use a little wine for the sake of your stomach and your frequent ailments.” If words, speech, and text is water, the idiosyncrasy present in every text or speech is wine.

The more intimate a subject is, the less you need a machine to do your thinking and writing for you. You want to enjoy every affection and gloom that comes with living with your thoughts and emotions. By this, the realm of personal writing is secure from the threat. Only the commercial world is threatened. So yes, businesses will profit from needing writers less. But humans, operating in the realm of the individual—the now scarce concept of the inner life, will continue writing for the sake of the subject because their thoughts and experiences seem to them worth communicating. I don’t want to chat with you for instance if you think chatGPT will render writing irrelevant. It only means you lack thoughts and experiences worth communicating. Conversations are only as spicy as the people who engage in them.

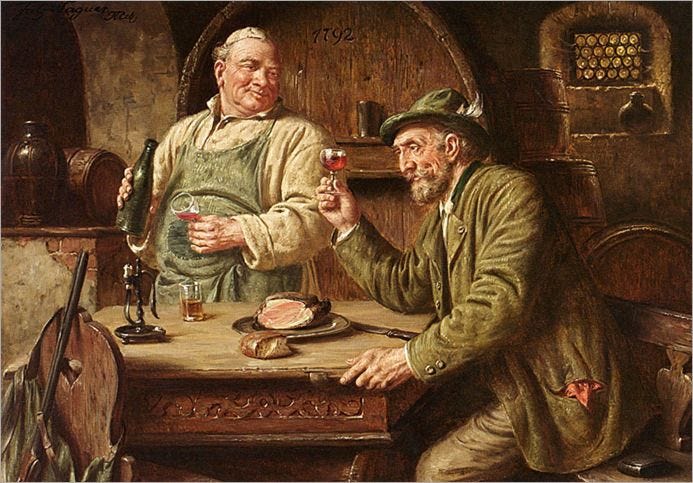

As I have noticed and as you may have too, conversing with different people on the same subject all have their uniqueness. Everyone brings a different flavour to the matter and allows it a sweet taste overall. We could all read the same book and we will perceive it differently. As such, if words were tasteless water, human eclecticism—drawing from a barrel of personal experiences—is wine; wine brewed and barrelled from different experiences in one’s lifetime. Yes, ChatGPT can spit out a poem. But did ChatGPT’s child die? I do not doubt that ChatGPT can say “Death be not proud” or anything like it. But did GPT lose six children such that when you return to the poem, Death be not proud wears a different, vivacious colour, not of grief but of a tongue scorning death? I think not.

I get it. Some of us enjoy being prompt-gods—we tell the machine what to spit out. We congratulate ourselves on our specific wording that generates genius vomits from the machine. However, some of us are compelled, obliged, to apply our hands. The craft is in our fingers and we must perform it. We will either make it or not have it. We have thoughts of our own worth writing and we enjoy the product as well as the process. This is the artisan’s way. By separating the process from the product, we arrive at the current panic.

The panic surrounding what AI will achieve—of displacing human writers—is the expected effect of reductionism. It is the fear that follows the thought that all we see is all there is. That what goes into a process matters less. Or that what we can measure is the only thing that matters. So, once you think of writing as mere information transfer—the measurable element, divorced from the elements of style—the immeasurable element—which Schopenhauer calls “the physiognomy of the mind,” you embrace the panic.

Perhaps we should learn from wine tasters. We should glean something from the sniff, swirl, and sip style of wine people.

Every normie thinks “It is just wine; drink it for God’s sake and let’s get on with it.” But why listen to the normie? He is already normie, normal, and boring, offering no excitement. I might as well do something different and see what this wine-obsessive has to teach. Why does he sniff the wine? What secret does he have that can transform the taste of wine on my lips from mere fluid to a heavenly drink? In other words, what is this magic?

In the same way, I could say to a book-taster: “It is just words; read it for God’s sake and let’s get on with it.” But I am already a normie, normal, and boring, offering no excitement. I might as well do something different and learn what this obsessive writer has to teach. Things like: what moves you to write when chatGPT can write for you? What do you know that can transform the sound of words in my head from mere text to life-breathing? In other words, what is this sorcery?

As water has no real excitement unless one is thirsty, information is not all-in-all unless I am desperate. And thank God for the internet and the abundant information on it, I am not desperate for information. Afforded this luxury, I am free to enjoy texts in the same way I would wine: sniff, swirl, sip, and slurp. I could go off pompously in a British accent on the wine: “This is a true 1868 Chateau Lafite Rothschild.” Or even better while writing this essay, I became a wine-tasting expert by watching a two-minute YouTube video. Does it get better than that?

Don’t fear what chatGPT brings. If you have anything worth writing, write. Be they thoughts, ideas, and experiences. If chatGPT and its cousins can upend your desire to write, you are better off not writing. You must retain your unique impressions without fear that the machine will outdo you. This is where your ego comes in.

We do not write only because what we have to say is new or unique. We write because we insist that we must share our thoughts on a subject despite all that has been written about it. We insist. And what if a thousand authors have written about writing? I want to write about writing. We insist upon it. And what if a thousand winemakers have crushed grapes before me? I want to crush my own grapes with my own hands. That is why we write.

Like water like wine, like AI like man. Give the machine time and let’s see if its works will age like wine. Until then, writer, keep writing.

Feast on wine or fast on water,

And your honor shall stand sure

If an angel out of heaven

Brings you something else to drink,

Thank him for his kind attentions,

Go and pour it down the sink.~ G.K Chesterton, Feast on Wine

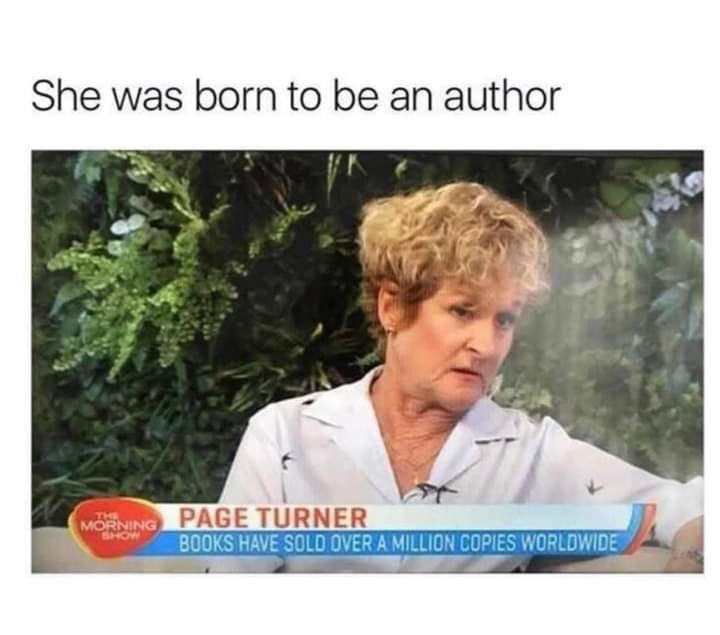

Welcome to August. Here is your meme:

Thank you to Latham Turner—I do not know if he is related to Page Turner above—for his feedback that inspired clarity.