Seneca's Toys

Most of what makes good thinking is categorizing things appropriately; like a dutiful librarian.

You are welcome to the dubbing and unveiling of my mental model. Well, not technically mine. But the naming is something I am proud to do by the powers vested on me by…well, me.

All mental models do the job of framing complex concepts in simple ways that can be learned and transmitted for use. Examples include The Baader-Meinhof effect, “The Map is not the territory,” Goodhart’s law, and my personal favorite, Chesterton’s fence.

In the past weeks, however, a certain model has stood apart in my heart and mind, conspicuous, as if begging me to see it everywhere and pay attention. It begged to come alive; to be useful. I heard its cry and I began the process by writing Selah.

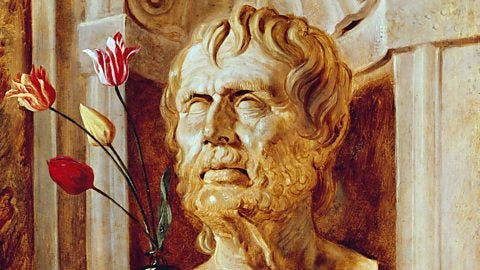

I wrote Selah as an attempt to put the problem of “have or need” in its rightful category. And I have mulled over it since then. Having found a quote that summarises the problem of “have or need,” I dubbed it, playfully, Seneca’s Toy. Seneca’s Toys states that:

Until we have begun to go without them, we fail to realize how unnecessary many things are. We've been using them not because we needed them but because we had them.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca

Seneca’s Toys

Rise, Seneca’s Toy, rise to honor and glory. Rise to your new name. Rise and serve your liege. Rise and take your rightful place amongst other great mental models in the intellectual framework of men. Solve the Problem of “have or need.” Set men free. Rise!

Okay, now back to reality…

It became necessary to dub this quote as a concept because we get many things wrong. We get it wrong in the sense that we think we use things because we (absolutely) need them whereas we use them because we have them. And that is putting it mildly. A little stretch down the road is the assertion that we don’t just use them because we have them, we seek out places where we must use them; even when there is no need at all.

We already to a large extent understand the concept of using things because we have them. How? We know Maslows’s hammer: If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.

However, Seneca takes it one step further. He deems some things as unnecessary. Yet, we keep them around like they are necessary or even important. For instance, we treat Instant Messaging apps and functions as integral to our relationships. Now, this isn’t bad until you realise that for some of us may break into fits and panic if in some time we do not get a response to our message.

Another instance–and a more serious one. The “fact” that a fetus at 6 weeks does not have a heartbeat is irrelevant to the abortion debate. Very irrelevant. I had never seen a bigger waste of argumentation in my life up until that point. Yet both sides of the divide tussled that trivial fact as if it were important; as if it was the decisive fact. I was horrified. Those who came upon the “discovery” (like Stacey Abrams) touted it like the salvation gospel (but make it “science”). Then I realised that sometimes, facts make people less sophisticated than they appear.

The inability to separate the useful from the trivial is a problem; a plague if I should say. This was my point in The Age of Cats and Shining Objects. We chase every fact that shines and forget the less salient things that actually work. We need help.

Most of what makes good thinking is categorizing things appropriately; like a dutiful librarian.

Have a leisurely weekend.