“Honey, does this make me look fat?” my wife asked.

I looked. Yes, I looked. And judged. I hummed for a few seconds, looking at her intently to see whether the dress made her look fat. Gathering my answer, I responded.

“Yes,” I submitted my scientific report. Detailed and well done. “Yes, I suppose it makes you look fat.”

My wife’s face dropped. That was not the happiest look on her face.

“You didn’t have to say anything,” she said as she aggressively picked up a comb from the table and walked quickly out of the room.

Myself, a man, wondered what I did wrong. Curious, I pursued.

“What? What did I say wrong?”

“Nothing.” “It is nothing.”

But I knew, that while nothing is indeed nothing metaphysically, this other “nothing” that was prancing around my cottage was no ordinary nothing. It was something; the real “why is there something instead of nothing?” Excited to get an answer, I pursued relentlessly.

Catching up, seizing her arm, I prodded, “Tell me, what I did.”

With such feminine fire in her eyes and cute dragon breath flowing chillingly out her nostrils, “If you knew it made me look fat you should not have said anything. Or at least say something nice. You know how I feel when I add weight. I already know I have gained some weight; I didn’t need you to sound it into my ear.” She said, as she folded her arms and dusted the cushion with vengeance.

I sighed. My time had come. I sat, pulling her hand after me, pulling her to sit on my lap. A man must often talk to his wife while she sits on his lap. God has made it so.

“You know,” I said after I had cleared my throat twice, while she looked straight away from me, reluctantly resting on my body, “I knew you wouldn’t love to hear yes.”

“Oh,” she said, judgingly, turning slightly around to judge me with her gaze. ”Then why did you say it?”

I shrugged. “Because it is the truth. The dress does make you look fat.” I shrugged once more.

“But who said I wanted to hear the truth?”

“You might not want to, but you need to.”

“Well, not in this case. The truth is not really what matters here; it is not a matter of life and death. You only just hurt my already hurt feelings.”

“Who said it is not a matter of life and death? It is always a matter of life and death; it is just not a matter of life and death in the moment. But the truth, however small, is always a matter of life and death.”

She huffed, puffed, and asked “What are you even saying? How does a simple question about a dress making me look fat become a matter of life and death? How?!” She huffed and puffed again.

I sighed.

“It is,” I restarted, “it is a matter of life and death because I want my words to mean something to you. Because I want to save up enough integrity for the day when it matters most. Consider that you already know that the dress makes you look fat. Yet, if I told you otherwise, that no it doesn’t, you won’t believe it. Will you be slightly happier? I guess. But will you trust me more? No. Unconsciously, somewhere, you will even trust me less. However, it still looks and feels like nothing. Just until the day when what you need is the truth.

“Suppose one day, your entire world crashes in, you feel insecure both inside and outside, and you are utterly convinced that you are no longer beautiful, and this is tearing you apart, mocking your world. Would you trust me to give you an honest opinion? If at this point, even the voices in your head and your very eyes are lying to you, could you turn to me to tell you the truth? And suppose that you do look beautiful, as opposed to your lying eyes and deceitful mind, will you trust me, if, after years of flattery, I tell you that you indeed look beautiful, will you believe me? Will not the voices in your head conspire to say this is just my latest attempt at flattering you; at telling you what you simply wish to hear? Will flattery save you in your hour of need?

“If, however, I always told you the truth. And you know me for the truth, regardless of the circumstances, tasteful or not, however the opinion is, will not my opinion carry greater weight than your lying eyes? Suppose I say it quite emphatically, with my ever truthful tone that ‘honey, you are still absolutely beautiful and I will swat anything that makes you think otherwise,’ will not my opinion restore much sanity to your falling world? If I always told you that ‘this looks good on you, but that doesn’t look good on you,’ will you not trust me when I say, rather unflinchingly, ‘darling, you have never looked better,’?

“This is what I aim towards: to be a man whose words you can bank on; whose utterances you can trust; whose opinions you can use as an anchor in turbulent moments of life. My word is my bond, and for life and death, good or ill, I intend to shore up my words with concordant integrity. So, do not be hard on me my dear wife, this dress might make you look fat, but you are no less beautiful; only more.”

After this, before my pouting wife could respond, I woke up to mosquitoes in opera at my bedside, entertaining me, a prime bachelor.

This is a trustworthy saying: honesty is a long-term investment. Integrity and a good reputation are worth more than gold and silver. This is a fact for all ages and a perennial truth in all seasons. Even if it fails to appear so to the myopic man.

Honesty is an investment. Honest men know it. Dishonest men also know it. Honest men know it, not by thinking of one day when they might cash in on their honesty; rather they take a deontic stance to honesty no matter what.

Dishonest men arrive at it quite actively. But late, and with an emergency, when they need the reputation of an honest man to slap as a seal of approval on their ongoing evil deeds.

This is true: dishonest men dislike honest men. For honest men deflate their plans. No one comfortably plans evil in the presence of a good and honest man —before a man of integrity. So, dishonest men dislike honest men. But they love and want their honesty; although not for the sake of learning honesty, but for the sake of scavenging that honesty as a ribbon or badge of approval for their dishonest gestures.

Shakespeare, voicing this idea through Casca concerning Brutus in Julius Caesar, said,

Oh he (Brutus) sits high in all the people’s hearts; And that which would appear offence in us, His countenance, like richest alchemy, Will change to virtue, and to worthiness

This event might not be fact but it is true nonetheless. It is a fact of the human heart: even the most vicious of men understand the value of honesty and a fine reputation. A good reputation brings a temporary fine scent to an odious enterprise. An honest man’s presence at a conspiracy lets onlookers think there might be some good in it.

Shakespeare still further speaks through Metellus, looking to latch on to Cicero’s reputation;

O let us have him, for his silver hairs Will purchase us a good opinion, And buy men’s voices to commend our deeds It shall be said his judgement ruled our hands; Our youths and wildness shall no whit appear, But all be buried in his gravity.

Be it silver hairs or a good countenance, dishonest men are hounds of virtue. They catch the scent and hunt it for game. This stands, however, on the basis that the honest man has been honest in the long-term, unwavering, having held his integrity before all, accumulating credits and respect over the years, even from people whose dubious plans he has wrenched with his honesty.

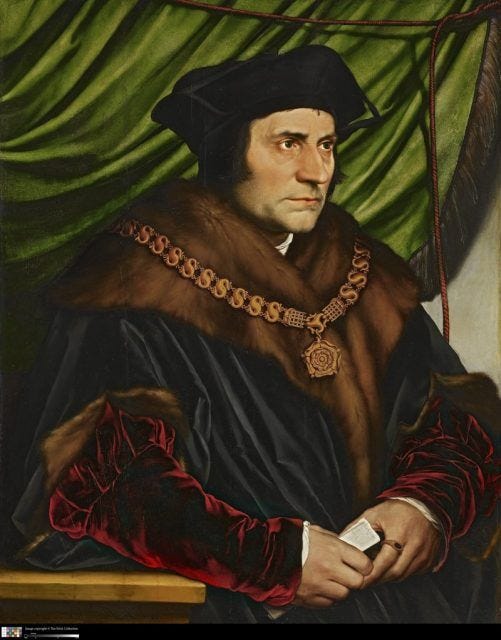

Was it not for his honesty that Henry VIII wanted Thomas More’s approval at all costs in putting away Catherine of Aragon? As this dialogue written by Robert Bolt demonstrates:

Henry: It is my bounden duty to put away the Queen and all the popes back to Peter shall not come between me and my duty! How is it that you cannot see? Everyone else does.

More: Then why does your Grace need my poor support?

Henry: Because you are honest…and what is more to the purpose, you are KNOWN to be honest. There are those like Norfolk who follow me because I wear the crown; and those like Master Cromwell who follow me because they are jackals with sharp teeth and I’m their tiger; there’s a mass that follows me because it follows anything that moves. And then there’s you…

Somewhere later, Thomas Cromwell says this as well: “The King wants Sir Thomas to bless his marriage. If Sir Thomas appeared at the wedding, now, it might save us all a lot of trouble.”

As it was with my fat wife, with Cicero, and with Sir Thomas, so it is in all of life. Men might despise honesty day after day, right until they need it. Be it for good or sinister ends. And when that day comes, assuming they haven’t stored enough grains of honesty in their warehouses, they will cry desperately for it —although not for it still, but for its fruits.

Should we then treat honesty as a long-term investment; teaching our children that one day honesty might just pay off? Are we to make the fruits of integrity its goal?

God forbid. For this is exactly how we rear a dishonest populace. A people who invest into honesty for its social and material gains often cash out despair. Their gain is usually a loss of hope and the damaging of faith in virtues.

It is not uncommon to hear people say being kind “doesn’t pay,” or that speaking the truth does not necessarily set you free. My school teachers used to say, “Tell the truth and the truth shall set you free,” making an abomination out of Jesus’ “and you shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free.” Students often spoke the truth and admitted their culpability so that they might regain their freedom. Alas, speaking the truth always brought them punishment. And with their original sin looking to pounce upon such a circumstance, the students often resolve that they will lie their way to freedom next time.

Therefore, it is wrong to attempt to cultivate virtue in a people by selling them the worldly good virtue often brings. It is a bad way to teach virtue. Which often is a way of selling virtue for its parts and accessorizing it.

Now I wonder if a man who strives to live an honest life for the sake of its payment on some auspicious day is really honest. Is he, not much more a schemer who hopes that one day, after he has accumulated this pile of reputational credit, will one day spend it slyly on some sinister gain? Is, therefore, a whole commitment to honesty whatever the cost and price a condition to call someone an honest man?

Perhaps this is where conscience comes in. But I hesitate to even think of conscience at a time where so few recognise the inner life of man or even actively denigrate it as non-existent. Yet one thing is true, from a first-person point of view of his own thoughts: a person who lies, and makes a habit out of lying, pulverises his will, and increases the tendency of lying so much that he will be the first to believe his own lies. Consequently, he begins to live in a constructed world that bears little correlation to the real world. It is a wonder if such a man can live with himself.

this is wonderful