“And some things that should not have been forgotten were lost. History became legend. Legend became myth.”

—Lady Galadriel

For a lively break from my treatment on the more sombre subject of abortion and the malice of wicked euphemisers against embryos with severe anomalies detected in utero, allow me to reflect on a less sombre and more colourful subject. On the subject of whether husbands are glorified errand boys. A sentiment I picked up while listening to a gentleman in an interview who was asked to share his experience as a new father and the challenges he faced.

This interview has racked up its fair tax of controversy in months past; and is no concern of mine, really. (In fact, you will find at the end of this essay that the sentiment itself is only fodder for some other agenda.) What concerns us here is that the man, sharing his experience, said that husbands are nothing but glorified errand boys. And overlooked errand boys at that, as most of the attention is focused on the postpartum mother.

A statement which earned its commentary —in the common frame of everything published on the internet. A vast portion of people thought he shouldn’t have expressed it this way. After all, his wife, who had just given birth to their child, needed him.

I take a slightly different view. But before relaying it, I ought to say that for a fair share of my young life, I have been far too exposed to the pessimism of husbands and fathers. Not very many of them exude the dignity I am certain is bound in the status of “father.” To be a husband and father, to too many men than I can count, consists in some sort of emasculation, one in which they seem to take pride. For it is overrepresented in voices loud enough, men who are willing to be carried along the tide, named “happy wife, happy life.” Men for whom and in whom leading their families is the human analogue of a reluctant ox plowing a field joylessly.

To be sure, the reader must not hear me say that these men are not good husbands and fathers in the sense of fulfilling their duties faithfully, albeit quietly. I am not requesting a boisterous declaration either. Rather, I am asserting that they might be doing so —fulfilling their duties— faithfully and quietly while portraying it bleakly. As a drab and undignified necessity. For I have learned to flee the scenes where a man begins to say “happy wife, happy life” or “just do what she says.” Regardless of how long they have stayed in the marriage. This drab pessimism, I suppose, is where I might file this same sentiment of the husband being a glorified errand boy.

I surmise that the type of mind and age that produces sentiments as this must be a mind and time incapable of the poetic, staunchly prosaic, and almost irredeemably mechanistic. I surmise also that things have not always been this way: we have not always been this prosaic and mechanistic and less poetic as a species, and this is the recipe we have lost.

When I hear, for instance, of the creed of medieval quarrymen, who, cutting mere stones, envisioned cathedrals, or the builders of Gothic cathedrals with their savage and obstinate love of nature poetically printed on stones as John Ruskin details, or the sea-shanties of sailors, I am all the more convinced that some thing was lost. And its absence has made our time harsher to cope with, despite all the seeming progress of which we boast.

This thing is the poetic mind. And also the land of spirits. And the perilous realm of fairies. And the warm presence of God. For having assumed that the world is nothing but a well-ordered machine, we have driven away all forms of true poetic entities; we are left with dead matter and a mind of wheels and metals. That’s why we can say that the husband is a glorified errand boy.

Too many times, we are quick to think that when the events of life have an unpleasant edge, the best action is to remove the unpleasant edge. But we are slow to think, and this is our real error, that maybe it is not a matter of what is present, but a matter of what is not present. By this I mean that it is the actual situation, a good deal of the time, that it is not that motherhood is hard, or that fatherhood is thankless, or that being the first kid is too harsh a task. Or, in this case, being a husband is servile. But those things which make perseverance possible, which cushion, lubricate, or dignify, are missing from the mental ensemble. Maybe, just maybe, it is not that being a quarryman is hard, breaking stones, but that the quarryman has lost the eye that sees the Cathedral. As such, it is not my intent to say that the task of husband and father to a vulnerable postpartum wife and mother is not arduous and taxing. But that the dignity of the patriarch is amiss.

The seat of husband and father, as I have come to learn, is the seat of principle; that is, that from which things proceed. It is the imitation of deity, as St. Thomas says, after God, it is one’s parents. For even Christ, God Himself, says, no one should sin against his parents, committing Corban, by using God as His excuse. It is a hefty seat weighted with dignity; dignified enough to pump a man with thumos enough to shoulder boulders for his wife and offspring. How then do we reduce such an exalted estate to nothing but errandry? I know how: by losing what it means to be and retaining what it means to do; retaining agere but neglecting esse. Whereas, agere sequitur esse (“to do” follows “to be”).

When one is preoccupied with and swallowed up by doing, left with no leisure or Sabbath to contemplate being and ‘mere’ existence, being is lost. And the buoyancy which being gives to the soul in the form of rational light. When the vision of the patriarch’s dignity is lost to a world that has nothing but fangs and daggers for the term ‘patriarchy,’ it offers no surprise to see that a man, father, and husband waits for applause like a Golden Retriever. (I am not surprised as well that there are women who pray to God for their own “Golden Retrievers.”) Such a man is a victim of an anarchical iconoclasm which shatters the noble image of what it means to be a principle and archon, and to have left him with the blurry fog of the managerial “servant-leader” in its place. When a man says being a husband is nothing but being a glorified errand boy, one would be tempted to think he wants gratitude. I dispute: he is starved for nobility. He is not looking to be honoured; his manly heart is hungry to be honourable. He doesn’t just want to be valourised, he wants to be a man of valour.

The stage was well set for this catastrophe. We exiled the enchantment in things and mechanised the human spirit. We gave ourselves to training for occupation and forgot to be men as men. We built the machines and then tried to make ourselves in their image; so we locked ourselves into their way of being and allowed for no surreal events; events that interrupt the normal way of things. We banished the Hobgoblins and set ourselves enemies to unusual surprises.

Somewhere at the back of my mind, I can hear that common cynical song rebuking my boyish idealism. It goes like this: “Ah, yes, when one is young, one has these ideals in the abstract and these castles in the air; but in middle age they all break up like clouds, and one comes down to a belief in practical politics, to using the machinery one has and getting on with the world as it is.” (Taken directly from Chesterton). I reply that “I have grown up and have discovered that these philanthropic old men were telling lies. What has really happened is exactly the opposite of what they said would happen. They said that I should lose my ideals and begin to believe in the methods of practical politicians. Now, I have not lost my ideals in the least; my faith in fundamentals is exactly what it always was. What I have lost is my old childlike faith in practical politics. I am still as much concerned as ever about the Battle of Armageddon; but I am not so much concerned about the General Election.” (Directly from Chesterton still.) With Chesterton I stand.

I am still as idyllic as I was. No. More idyllic than I was. My idyllism grows with my potential wrinkles and greys. Which is why I am eager to set forth the capsule I think is good for all men to swallow. We must do fairy tales again. We ought to see boys grow on a staple of adventure and chivalrous tales. In doing so, we will set forth a new image for them to behold and be formed after. So that when they set out on errands for their wife and the mother of their child, they are consumed with the nobility of their being as it is transmitted in the valour of their task. Rather than be an errand boy, he desires errantry. Rather than go out to buy baby food, he wants to win his lady’s honour. In other words, the boy wants a richer mind and a noble heart.

Our current day revolts against images. Especially the image of God. It hates the symbols which pay no homage to the machine. It destroys the image of God as printed on the male and female bodies. It despises the image of God’s kingship emblazoned on human kings; it despises the image of Christ, the Redeeming Husband, by demeaning human husbands and trashes the church by fueling reviling wives.

But what boys and men need is the image of Christ, the saviour husband. For when next the man has to go bear up under harsh conditions to see that his wife’s needs are met, he ought to see himself participating in the Christly paradigm of laying down his life for her, picking it back up, ascending into heavenly places, and riding once more in a triumphal procession. Valete

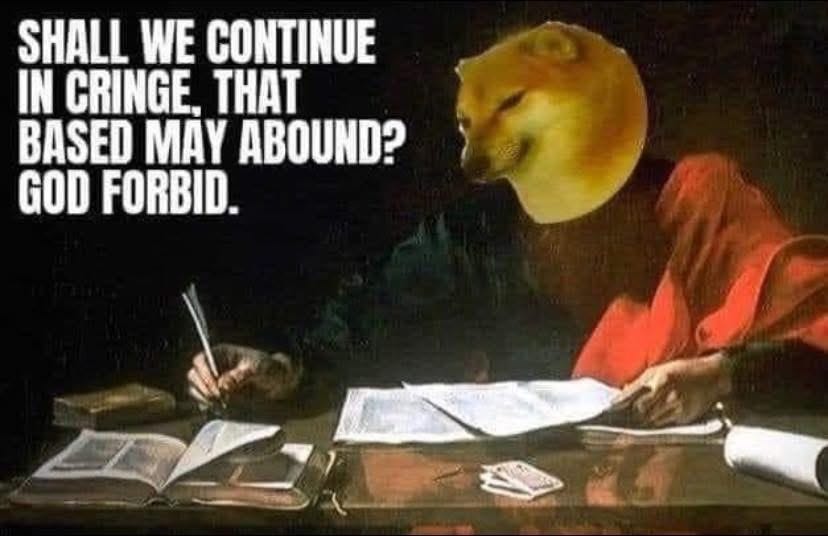

A meme, let us pray:

“In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

The Abolition of Man

C. S. Lewis

busymimds, you bad gannnn