On Abortion and The Commercialisation of Virtue

“Parents are not interested in producing the ‘complete man’ any more. They want to qualify their boys for jobs in the modern world. You can hardly blame them, can you?” —Evelyn Waugh, Scott-King’s Modern Europe

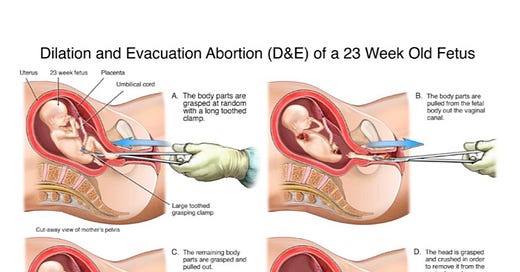

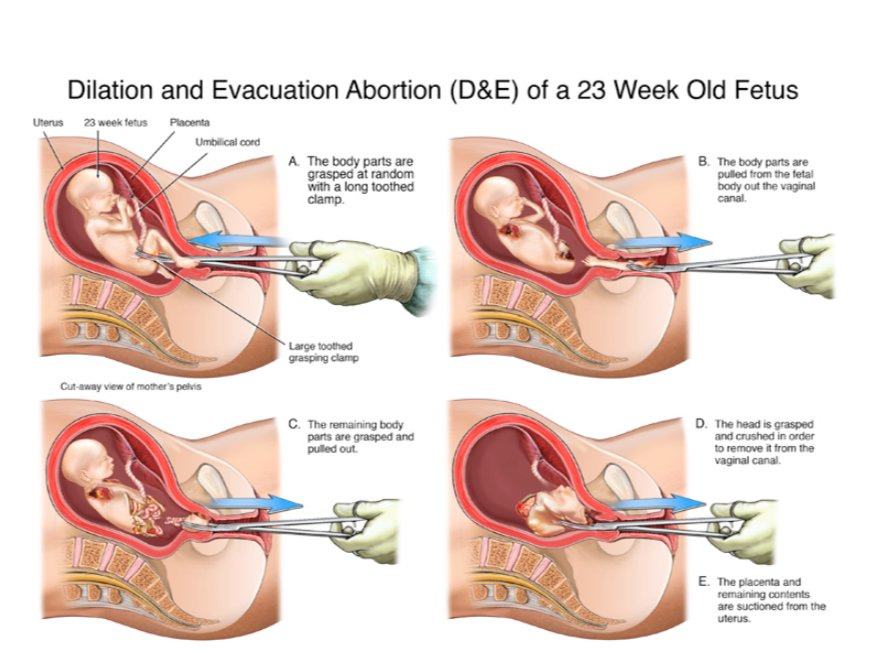

Abortion is the activity of our time. By this, I mean foetal death and dismemberment. For when I read of the horrors of abortion; of how the foetus is crushed, torn, and taken apart limb by limb; of how some people do it with glee and think it a human right to be so cruel, I shudder. The true and tragic picture of the procedure, if you see it, ought to demolish the euphoric euphemisms pro-abortionists paint it with. Like calling the foetus a “lifeless clump of cells.” How these people live with themselves; and what they see in the mirror, I cannot tell.

Yet now I see something else: that the babies in the womb are not the only victims of this horror, But the world and the concepts through which we touch the world are themselves victims. We have perfected the habit of taking the concepts crucial to man and meaning, and have torn them limb by limb for sinister ends.

One such concept through which we touch the world; upon which we have enacted our barbaric acts of abortion is virtue. For like a baby’s body, true virtue grows as a whole, integral and integrated. Virtue is whole, all member parts —charity, temperance, prudence, courage, and the entire cohort—working hand in hand. But like the helpless foetus, we have crushed and taken them apart limb by limb. And like the people of business that we are; with our throbbing pulses of utilitarianism, we have put pieces of virtue up for sale —as we have done with aborted foetal tissues for medical research.

This shows in the way we describe the benefits of virtue. Not that man must live virtuous, and end it there. It is out of fashion to say “one must pursue virtue.” Instead, we get endless justifications as to why we ought to develop a certain strip or limb of virtue. Virtue becomes a means of social advancement. You no longer have to be courageous—because it is good and necessary to being. Rather, courage is how you “make it in life.” It is how you “do what everyone else was afraid to do” and succeed. Virtue becomes a “leg-up” over others. In other words, we come to know virtue, not by its merit and intrinsic need for man’s soul, but by its market price. By the material goods the particular virtue affords the owner. We say “attitude determines altitude” to compel boys to develop character traits that allow them admirable social status and prominence.

The merchant does not say “Be virtuous my son.” No. He takes it apart bit by bit and shows you what you can purchase if you have patience or wisdom. He leads with the benefits: “You need patience to see an idea through”; “Wisdom will bring you gold”; now that I think about it, I have not yet seen what prudence brings to the current market— for it is extremes that make bank. He treats the different organelles of virtue as several entities which you may severally adopt or acquire for some mercantile and material objective. For this is the only way that virtue can go on the market; not as an integrated whole but as a dismembered entity. Just as a living foetus is unfit for medical research, virtue —in its integral form— is unfit for the job market.

This sense of abortion and the attending lack of the knowledge of integration reappears once more in my reflections upon a reflection. Once someone said that resilience is not an “unalloyed positive, but really they are value-neutral.” By this she meant that resilience is ‘neither good nor bad, it only depends on what you do with it; it may be a virtue or a vice,’ a statement Mr McLuhan would call “the voice of the current somnambulism.” As the reader may guess, I objected. Resilience is an unalloyed good. It is good through and through. Yet I understand our author’s concerns. For she spoke in the context of the Nigerian people who are capable, by means diabolical, of enduring just about any scorpion the Nigerian government whips them with. Nonetheless, I refuse to cede ground that resilience is an unalloyed good. What misunderstanding we have then, comes from the fact that we are missing something from our permutations: the integral nature of virtue.

As I argued, “We will be giving resilience a bad name if we think resilience is some form of eternal perseverance.” Because a mix of foolishness and the ability to adapt to a given situation is not resilience. It is not resilience to endure and adapt to a situation that demands your changing it. However, this goes unheard in light of our current predicament; where traits are treated in isolation from other traits.

Therefore, resilience is no resilience when it ceases to function in the embrace of temperance and courage. Where the character is divorced from its object of consideration. If resilience lacks wisdom, or if it fails to operate within its ambits, it has become something else; something lower and decrepit like an overworked ass that cannot rebel. Operating this way in men, you cannot call it resilience as the men themselves are denatured, reduced from humans to subservient beasts of burden.

Or maybe we can call it resilience in the same way you call an amputated leg a leg. Truly, a leg removed from the organic whole is a leg. But a leg now in a different sense. If not artificially preserved, will begin to rot. And it is no longer a recognised leg in its healthy sense. Unless labelled, we don’t know whose leg it is. You may put it on display. But it is useless. Of what use then is your resilience?

Taking this Harvard Business Review on The Dark Side of Resilience, for instance, you see our diagnosis reflected therein. The writer summarises the article thus: “There is no doubt that resilience is a useful and highly-adaptive trait, especially in the face of traumatic events. However, it can be taken too far. For example, too much resilience could make people overly tolerant of adversity.”

Clearly, the writer pays little attention to the denaturing an object undergoes when taken to an extreme. And resilience, removed from its community of other virtues appears problematic, mirroring our initial author’s thought that resilience is no unalloyed positive. What this line of thought often shows is that the speakers are too aware of what is present and totally unaware of what is missing. And this is an important point: someone missing two legs, and resorts to moving on his hands thereby deforming the hands in the long run does not make the hands bad —or “value neutral,” —it makes it do what it isn’t meant to be doing for it is not a leg.

Thus, such sentiment expressed as the value-neutrality of virtue is what we must come to expect for a world that does not deal in wholes but in parts. For we make no profit off of them when we sell them whole. You may find this with smartphones: as they advance, they strip the phones of parts that used to be in them before —earphone jack for instance—and sell accessories in a different package. Cars are now to be unlocked as you go with software updates, leaving you at the mercy of the manufacturer. You pay huge sums for video games yet you do not own it. We live under the yoke of endless accessorizing. But we ought not to expect less from a world surmounted by profit-orientation as its apex goal. Babies are useless; except for their parts. Virtue is not a need unless you are vying for advancement in life. Nothing is good except it is sold for its parts. What a world, that “knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

And for a world that has sold virtue for its parts, we cannot recognise that sometimes it isn’t about what is there but about what is missing. It is courageous, for instance, to face the crowd when it is good. It is also wise to flee the crowd when the occasion demands so. This way, it is not courage to stand when you must flee, it is foolishness. To then slap a bad name on courage for the sake of a man’s foolishness is to do us all injury. It is bad thinking and living to divorce courage from its rightful object —prudent thinking, working hand in hand with courage because they function as an organic whole is to determine what you must flee from and what you must confront. This is clanging cymbal talk, however, to a time that has put salesmanship in the place of moral virtue.

For you cannot go on long without a necessary organ. You might exile virtue from our social life. But you cannot leave its office empty. Which is why we resort all the time to simulated emotions —call it empathy, emotional intelligence, and even resilience—to fill the space left. But a simulated organ, like the other horror of vaginoplasty, will never be a part of the organic whole. It will need telling and retelling, affirming and reaffirming. For due to its inorganic and artificial nature, it will decay.

What must be told then to an amnesic world is that virtue is whole and integrated. Repent from aborting and accessorizing virtue. Without virtue, man is not whole. Man disintegrates. Man will fall apart, he will not hold. He will not be at ease. Vale!

Interesting that I listened to a sermon recently that talked about the fruit of the Spirit and how it is a whole, not a segmented framework. Until we see that you cannot truly be patient if you have no kindness in your heart or be peaceful if you have no love, we can't claim to know the fruit of the Spirit. We've really become a world that deals in parts rather than in the whole.

This was a good read as usual 👏 Been a while.

Could it also be related to how we use words and language nowadays? The dwindling use of words as they were meant to be used? For example, rather than call foolish what is directly (in the case of the example you gave), we attach adjectives and call it "foolish courage," thus stripping courage of its initial meaning and canceling out its good while painting foolishness as something that has some semblance of goodness.

I don't know if you get what I mean