The Expert Problem

Monday Map

You are reading another edition of Monday Map. Today you will read about the expert problem, Goodhart’s law, and Why women’s tears win in the marketplace of ideas.

Read and enjoy. But before then, subscribe. And if you have subscribed, please share with your friends to read and subscribe as well.

THE EXPERT PROBLEM

“A broken clock is at least right two times a day.”

We use this statement commonly to depict that someone perpetually prone to error or ignorance can stumble upon the correct answer or opinion on a matter. But we don’t acknowledge the other side to this- that when a working clocking breaks but keeps working, we stand to lose a great deal. I will explain.

Imagine that your alarm clock still works. But by some fate it became faulty, wrong, and late, but still ticking. What are the dangers? Well, if it is one hour behind, then I may lose time and wake up late, get stuck in traffic, miss my presentation or a meeting, and if things are really bad, maybe lose my job or this life-changing contract. All due to a badly-working clock. With this analogy, I present the expert problem.

We trust people who study hard, commit themselves to a particular endeavor, become competent, prove their competence, and master it. We defer to their judgment when we are exposed to things we do not understand. By reason of competence, time and mastery, they become experts. But what is the expert problem?

The expert problem is the downside to the experts being wrong. Should we defer to their judgment in things that are consequential, and should they be wrong, we will suffer a lot. That is the expert problem.

Keeping to my tradition, I must address objections such as “but you are ignorant about X. so just the experts.” Or “your ‘research’ is nothing compared to the expert’s research. So just trust the experts.” Or even worse “you don’t have a PhD or a Nobel prize. So just trust the experts.”

I am not against trusting experts in whatever they do. I acknowledge and everyone sensible will acknowledge it too that you cannot learn everything to the tiniest detail. You cannot perform the extensive research, experiments, and studies that the experts put into their work. But I am saying that when the case is consequential, we must put less faith in the experts.

Using Goodhart’s law that “when the measure becomes the target it ceases to be a good measure,” it makes sense that we should find a more rigorous method of exercising judgment and decision-making in the highly impactful matters. When all a person banks on to become an expert is to get a degree (maybe a doctorate degree) in the subject, it becomes necessary that we have less faith in the ‘expert’ as we face an unstable/evolving situation. You may receive a Nobel Prize for an innovation and just be wrong about the next ten notable events after your outstanding work. It doesn’t make you less of an expert. It just shows how you are human and wrong.

A world that is constantly being exposed to novel events or modifications of past events is one that requires us to address it with as much evolution as it presents. That is, we will continually face areas of subjects that we either have not faced before, or areas that although we have faced them, they have developed some new feature or another.

Take COVID-19, it was definitely not so new. The literature identified it to be of the sars-cov virus class. Mr. 19 was just a new variant of this class. We are not new to wars and its dastardly effect. But the effect of the atomic bomb in the Second World War surprised the world and we still look back at this tragic wonder.

But how do all these tie in with the expert problem? Simply put: sometimes the experts do not just know enough or are wrong. And this incorrectness costs us.

People trust experts. And this trust is expensive. So it should break your heart and inject a little skepticism into your minds when you realize that some of the most tragic events in history have expert counsel behind them. You must look again.

Because this is not extensive, I am including this link to David Mamet Explains What Happens When the Experts Fail. It contains useful insights of the price we pay when experts fail.

GOODHART’S LAW

Essay writing exercises in school were aimed at making students competent and expressive in fluent language and grammar. It had that one aim: expression. But there happened to be a part of the requirement that derailed the aim and gave us a whole new target. It was the word count.

I write every day. But I do not restrict myself to a specific word count. Sometimes it might be a thousand words. Some days a hundred words is enough. The rest of this session explains why.

Goodhart’s law states that “when the measure becomes the target it ceases to be a good measure.”

So with the essay writing exercises, the target was to become expressive writers. But when given a word count obligation to fulfill, the initial target fades, and the measure becomes the target.

I know my secondary school teachers counted the words to know if I met the obligation. But I don’t think they cared about my ability to express myself. I was not concerned with expressing myself either. I just wanted to hit 500 words and bolt. And that is how Goodhart’s law works.

If you prescribe a measure for a target, human beings in our nice nature will find how to game the metric so that we produce the given metric most times at the expense of doing a good job.

If you give your plastic cup factory workers the target to make 50 plastic cups a day before they eat lunch, they will produce 50 cups. But can you guarantee that those cups are good cups? If you are more concerned about producing 50 cups before lunchtime, don’t be alarmed when the public sues your factory for producing poisoned plastic cups.

All I am saying and depicting with Goodhart’s law is that people have the tendency to game the metrics of measurement. Know this and learn to beat the grain and provide more complex metrics.

Women's Tears Win in a Marketplace of Ideas

Ok, this is an essay I read last week, written by Richard Hanania. It was an important piece that articulated some of my observations of how micro and macro society are structured to operate.

My takeaway is this: as the societal scope increases, we move away from the arrangement that favors the feminine temperament and defer more to a masculine way of doing things. The intended arrangement of the marketplace of ideas does not accommodate the feminine condition as much. Read and enjoy Richard's brilliance.

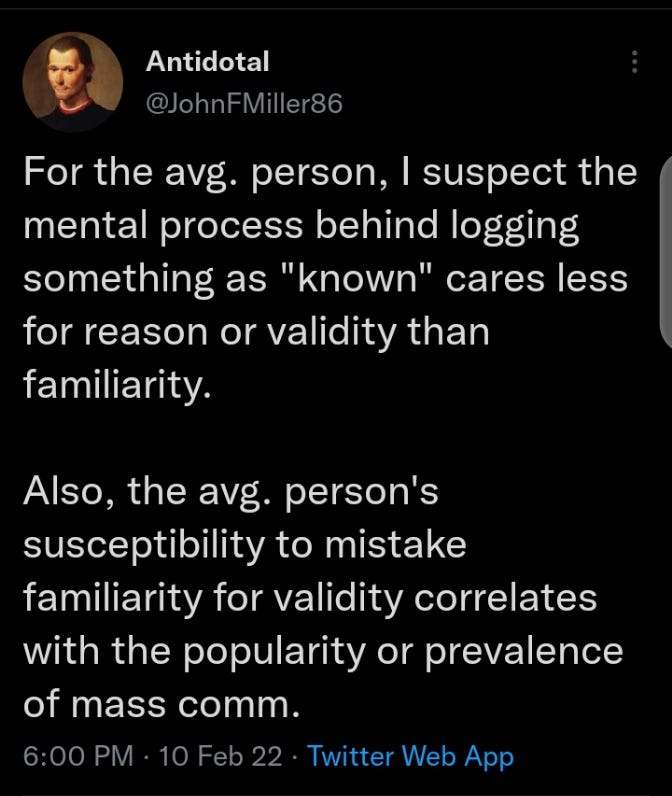

Of course, before you go, hold this picture:

See you this week.

Emmanuel.