Our minds have the bad habit of seeking extremes. One of those extreme-styled thinking is the “either/or” type. Where we find one correct answer to a problem and declare it as all there is. Sometimes it is a superstition and sometimes a sickness. It is a simplification of the maddest order. Like a child with small hands who cannot grasp many things; finding out that there are many balls to hold, instead of learning to juggle them, holds one tight and disposes the rest. He then whistles while hopping away happily ever after. It would have been good if instead of falling for “either/ors,” we should instead be greedy with causes and explanations. Holding out for a multitude of them, juggling them, and making them work for us.

One such occasion where the feeble world and its even more feeble thinkers enter into the extreme under consideration is in spotting what motivates a man; his desires or more generally the desires of mankind.

Our superstitious genes point us to one motivation over the other as fuel for an action or behaviour.

For instance, on matters of work and productive labour. The philosophers and men of leisure point to an innate need to work. That we love work. That we were made to work whether or not we need it to survive. That even in a utopia, we will work and excel at productive activities. They mention that we work, say tend a garden for instance, even as an act of leisure. That boys dig holes at the beach for the love of it. Ever seen kids? They plant seeds just because they have the desire to see an orange plant grow. The philosophers say that even without the burden of survival, man will work and get his hands dirty and labour and produce. On this point they are correct. Award this point to the communists.

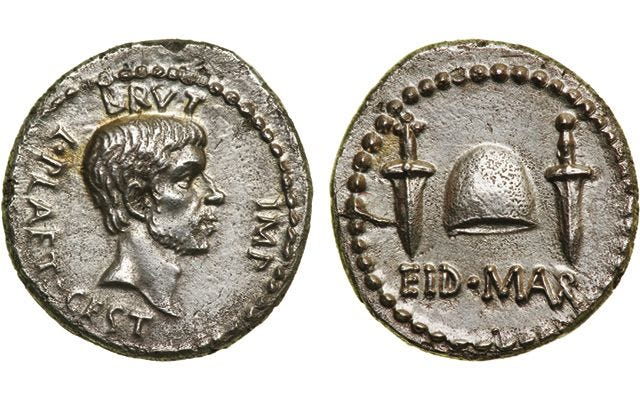

But on the other side of the coin, you have the labourers who think we must continue working because we need to survive. On this side of the denarius, they say—and they are correct—that we work because we must survive. That all work is geared towards survival. That everyone must contribute. They detest parasites—those who live on the work of others without contributing anything to the productive world. They may dislike welfarism. Harsh as they may come across, they are not wrong. We work because we must survive.

With the two sides of the denarius spelt out, the regular man compels himself to choose a side. To find his one answer upon which everything else pivots. And so the one drifts off into becoming a freak of leisure and the other becomes a freak of not-leisure. They either become Diogenes or they become twentieth-century communists; not living life in a delicate balance. And this is the common sickness of man.

What I see instead is that none of those desires themselves are fuel enough—like a weak male urine stream that tries to clean the toilet bowl. By this, I mean that no stream of motivation is strong enough to power and sustain behaviours. The innate need to work cannot produce the surplus we need. We must also work to survive; in a mater artium necessitas manner. But we will not always crank away endlessly in labour. We will also work from a place of rest and leisure keeping the worries of life and survival at abeyance. Both work together at their given moments.

Take the case of love. It is quite the fashion nowadays to insist that love is not an emotion when some people utter the stupid phrase “love is not enough.” The former fashion insists then that love is a duty, an action, a commitment. And that mere passion is not love. The way I see it, this fashion is one quite well dressed in our superstition under consideration.

Love is neither passion nor duty. Villains have passions and mercenaries have duty—duty to their stomachs and bank accounts. Love is not to choose either passion or duty. It is to have the two work together. Passion fueling duty and duty keeping passion in check. Because one wonders: if love is unconditional, why then do I have to select for traits in a spouse like they are some means to an end? (I assure you that most people have not gotten to this bridge of thought before so they would not have to cross it. They don’t even understand what loving someone as ends in itself means). So here we are fighting the battle within ourselves to love someone because they ought to be loved. But then she has great hips—you know, signs of fecundity. More generally, I think the answer to “Why do you love me?” is “I just do.” Yet, I think it is insufficient for making a lifelong commitment. You have the duty to choose someone who fits your values and goals in life. However, if you sat to observe the ruthlessness that goes into selecting an ideal spouse, you will be tempted to fall into a utilitarian frame of mind where who you are choosing for wife or husband is simply a means to an end.

So, again, love is neither affection nor duty. It is both. Upon choosing the best fit, you must start to love them as an end in themselves. With impassioned duty.

Sometimes passion fails. And many times duty breaks. This is only because we are human. We are human because things fail and break. But these things must not break at the same time. If not, the centre cannot hold. A man must keep to his vow of fidelity as an act of duty. But is it not better if he keeps them, not out of a mechanical efficiency; which stands the risk of rust and friction, but because his wife is his sole object of desire? Who says duty must be lifeless, passionless, affectionless?

When you look at a behaviour with a mind to determine its underlying motivation, I recommend you to henceforth keep in mind that you should anticipate more than one stream of motivation. Monocausality is rare. And no motivation is pure in itself to keep man consistent. By pure I don’t mean that a desire is contaminated. In this case impure is not the opposite of pure. What I mean instead is that you often have more than one motivation working—maybe two working together—to keep a mechanism or a behaviour in place.

You simply have to look at Christianity—and look at it well—to realise that love is neither duty nor passion. It is both. Love is not utilitarian. It is totalitarian. It consumes the whole man: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.” Love is passion with a direction. Love is teleological affection. True love always inspires and directs duty to an object worthy of it. But a sick mind, presenting as an endlessly analytic one, strips everything into bits and chooses “what works.”

As it is, some minds are more prone to the either/or sickness than others. All men think because we have minds. But we can say that there are two types of thinkers: those who think because they can; and those who truly enjoy thinking. The first kind wants to do it, be done with it, and perhaps get congratulated for doing it. They use the mind like a crude tool—something to be used without enjoying it. The others just love to do it. They truly enjoy thinking. The latter will fall less for the either-or pathogen.

It is the disease of the hyperanalytic mind to tear things into parts and strips without care that those parts and strips only work when they are joined together. In other words, the hyperanalytic mind cannot conceive an integrated thing. It lives and pants and laps like a dog for fragmentation. It wants to break everything into tiny pieces and congratulate himself with “nothing buttery.” Meanwhile, the world is an integrated thing. The human being is an integrated person. Everything works by being interconnected. And there are hardly any pure streams of desires.

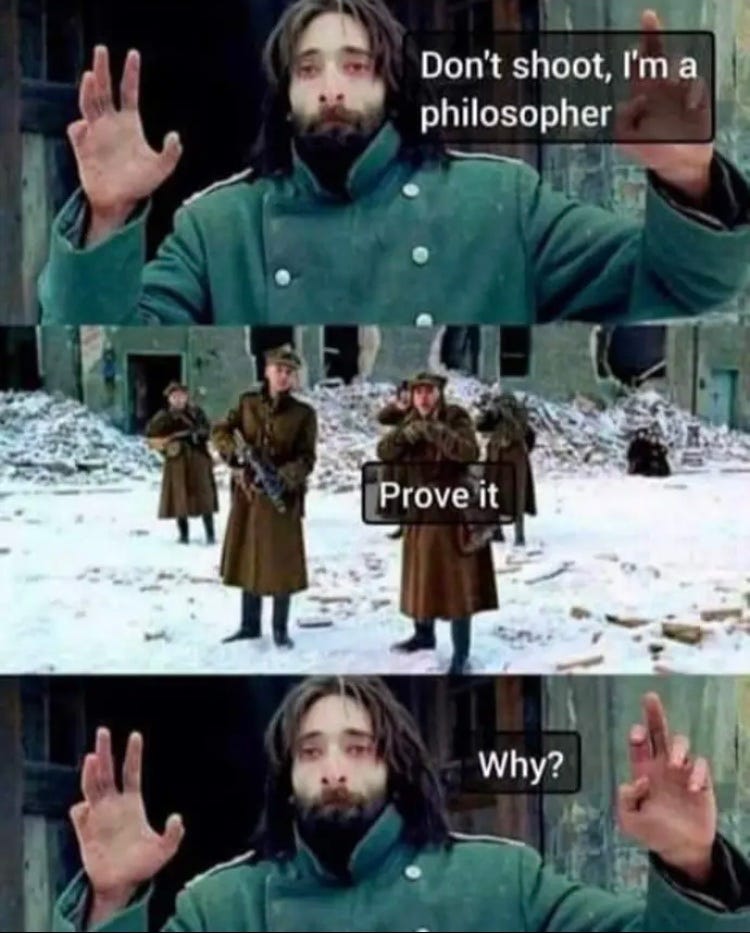

And here is your meme: