“Why avoid cliches?” you ask. “Why, as a woman who wants babies of her own, avoid a sterile man?” I ask in return. Because cliches are like a man “firing blanks,” sowing a seed, but the seed being unvital, cannot take hold and impregnate.

I say this sadly — as it is true of myself and for others — that many people think they think. That is, they are under the illusion that they think about things. That they conceive things. That they mull over things. And that they have made some concepts theirs. But if you would only listen to them speak of these things that they say they have thought about, you soon realise that their thoughts are borrowed. And those thoughts, as if they are animated with the soul of their original owners, scream that “this person who has borrowed me does not own me and that at any time I will betray them.” Nothing shows the illusion of thought more than employing cliches.

Cliches are dangerous to the extent that a woman thinks her husband is fertile. Certainly, they have good coitus. They roll and romp and moan in bed, not missing out on the sweaty pleasure that God has granted for Holy matrimony. But time and time again, we see this pleasure wasted in terms of procreation because the woman fails to conceive. Such is the case with thinking in cliches; or in borrowed thoughts and words: you enjoy all the pleasures of having participated in thinking. But given enough time, the fruit fails to show then everyone knows that something is wrong.

Consider the wonder that is language. Consider its purpose: I see something with trunks, bark, leaves, branches, and possibly roots. But my friend does not see it. Then I told him I saw a tree. And without seeing the tree, he actually sees a tree. That is the purpose of language. To transmit — in order to help someone see — what they have not actually seen. Language works for transferring concepts from one mind to another. It is in this manner that language is a form of insemination to the end that the receiver of the seed might conceive the information that the giver provides.

To that end then, language works to the extent that it impregnates. To the extent that the receiver “takes in”; to the extent that they conceive. And we expect that when they conceive, they gestate. And when the time of gestation is over, they will produce a young, offspring, especially one with both similarities and differences from the parent. And it is in this way that cliches betray an absence of thought. Anyone who uses cliches produces a clone and not a recombination of thought.

The dangers of cliches then lie in wasting everyone’s time. In giving everyone an illusion that they are thinking without actually impregnating their minds with—nor are they gestating—a concept. It is simply a sterile seed floating in your mental abdomen unable to charge an ovum with the necessary information. Then that air of familiarity that cliche brings is similar to the scorn a ‘barren’ woman receives from society. That scorn that painfully reminds you that you have received nothing in places where you thought you have.

It is the duty of anyone who thinks he thinks to avoid the overfamiliar when dealing with a concept. He must refuse to use popular or trendy language; clanking terms—those buzzwords that signal one’s familiarity with a mental terrain without acquaintance with the concept themselves. Find your own metaphors. Hewn your analogies out of undiscovered rocks. Write a Bestman speech entirely in mathematical symbols. Do the work. Think.

It is bad, while seducing a child into becoming a voracious reader, to tempt him by saying “Readers are leaders.” No, readers are not leaders. Or at least, that is not why we—those who live with our minds—read.

Fair enough, you may introduce the concept of greatness—that is leadership—to a child so that you might get him to start reading books. You might dangle the beautiful things of this life before him to start a good thing such as reading a book; stimulating his interest in books by telling him that Gates, that wealthy guy he loves, loves to read. But I fear that if the child is anything like me, he will realise that the statement “readers are leaders” conceals the dishonesty that flashes across the adult’s eyes like a wishing star. A dishonesty more painful than realising that Santa Claus is not real; or even worse, that communism does not work. He will apprehend, sooner or later, that “readers are leaders” is the intellectual equivalent of persuading him to eat broccoli. Then he, the child, will either hate reading, or he will like me, tell you, “I love reading even though I dislike leading.” He will say “I read whether or not I will lead.” He will realise that reading and leading are not so married by God that no man can cause asunder. He will see that they belong in their various places and they are only, merely friends.

It is true that reading and leading are merely friends and not spouses—where two become one. If you leave it at this, you can justify that leading involves a lot of reading. And that reading may eventually cause you to lead. But you can never in this way justify the tone that leading is why we read. Taken this way, “leaders are readers” is true and different from “readers are leaders.”

The child that immediately starts reading whatever his eyes see—Traffic Rulebook, Christian Women Mirror, the newspaper, and Hints magazine—is not interested in leading; at least not in that moment. It is not because he will someday lead his peers that he learns the word “boobs" at age eight. Even then he did not know its meaning. The child that tries to finish Harry Potter and The Prisoner of Azkaban in one day at age eight has no care for being a leader. The child that stays with Brighter Grammar and Queen Primer while everyone else in the house naps is not doing so with the intention to one day be the mighty prime minister of the nation. Far from it. Every book, or every text he grabs expresses a different, eternally relevant incentive: pleasure.

It is the child who has no pleasure to read that we tell that readers are leaders. The child who enjoys reading could not care less if readers are sufferers. In fact, readers suffer. But that pleasure is now and even if he becomes a leader, a lasting incentive. That pleasure—intrinsic pleasure we call it—is the fire of the life of the mind.

In a ceaseless war between technique and spirit, I ask myself if I have to choose between them. Without a doubt, I will choose spirit. Spirit is fluid. Technique is rigid. And for all I know; for all the things that are good as end in themselves, techniques and structures are not included. It is as much unwise to discipline for discipline’s sake as it is unwise to swallow drugs for drugs’ sake. Or to pray for prayer’s sake---this is what makes Pharisees: they pray for prayer and attention’s sake. As such, technique cannot justify itself apart from spirit or some other ends.

I know already, that I am opposed to the technique-optimiser. The person who engages in technique for technique’s sake. Who is pedantic for its own sake. Who has productivity hacks for reading books for its own sake. But then I am not opposed to technique. For I realise that techniques are how spirit accomplishes its ends. But it means then that techniques ought to be temporary. They cannot be eternal. In the sense that when what is permanent comes, that which is temporal may pass away. It is then dangerous for technique to exist longer than it should—that is after the spirit has come.

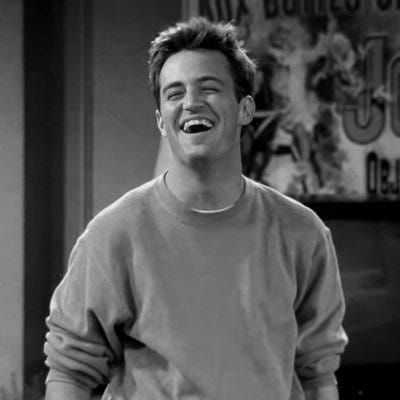

Rest Well Matthew Perry.

Cliches are like costly assumptions. Sadly, the price to pay is time.